Artwork: ‘Echoes of Freedom’ by Progga Protity: “This triptych explores the human struggle against imposed boundaries. The birds, caught in geometric constraints, symbolize lives shaped by borders—both physical and invisible. Yet, in their movement, there is defiance, a quiet persistence to break free and transcend the limits set upon them.” – Progga Protity

Questioning Borders? Borders and Human Rights

Originally published in 2022. Revised June 2025.

By Angela Ciceron, Sara Gibson, Shayna Plaut, Adele Perry and Pauline Tennent

There are borders of various kinds all around us, including the medicine line to the south, drawn awkwardly through and across Indigenous lands in the middle of the 19th century, and which continues to exert real and highly differentiated power over those who navigate it. The creation of these artificial borders here in Turtle Island, and indeed all over the globe such as the Scramble for Africa at the Berlin Conference (1884), has resulted in the partitioning and parcelling of land and communities shaped and supported by the role of law.1

But borders are not just those lines on a map that emerge naturally over time. As Harsha Walia2 reminds us, borders are all the ways in which borders, binaries, and ordering regimes of power and domination are enforced. The very real function of the creation of these borders is regulation – to regulate land and waters, humans, and animal relatives, all in ways that work to support colonialism, imperialism, and capitalism.3 We see this today as walls are built or reinforced to keep people out, while threats are made to annex other peoples and territories – with borders viewed as both fixed and malleable to the whims of state power.

The re-election of Donald Trump as US president in 2024 has driven home how borders function as conduits of power and authority. Baldly anti-immigrant rhetoric has re-emerged. It is backed by policy changes that have lead to more than 11,700 people being in US immigration detention in mid-June 2025. This is a remarkable 1,271% increase since Trump took office, and merely one example of a government targeting undocumented and migrant people.4

Trump’s longstanding promises to build a wall along the southern border is now accompanied by his interest in annexing Canada. The federal election of 2025 elected Prime Minister Mark Carney on a theme of ‘Elbows Up’ resistance to American tariffs and threats. The new government soon after introduced an omnibus bill promising to bolster Canada’s borders. As Desmond Cole notes, this legislation is in keeping with long histories of “Canada-U.S. colonial alignment on immigration that has historically led the two countries other than exclude and prosecute the same refuge-seeking populations.”5

The Centre for Human Rights Research, through the work of staff and students, research affiliates, and partners takes an intersectional approach to borders – understanding borders and human rights capaciously and always in conversation with Indigenous pasts, present, and futures, and to the knowledge that these frameworks are always best understood when they are gendered, racialized, and embodied. The CHRR works to support and expand research that explores the intersection of borders and human rights, including how borders may impede access to human rights or be a source of right violations themselves. We recognize that borders exist beyond the geopolitical boundaries of states – and that it is often the state that forcibly created the border in nations.

We also aim to explore borders that may not fit under the “traditional” border language. These include borders of Indigeneity, identity, gender and the body, virtue, race, and economy; all borders that manifest within and across empires and states. These are the borders beyond the geopolitical.

How to cite: Ciceron, A., Gibson, S., Plaut, S., Perry, A., and Tennent, P. (2025). Questioning Borders? Borders and Human Rights. Centre for Human Rights Research. https://chrr.info/research-theme/research-themes/boarders-and-human-rights/

The Geopolitics of Borders

Borders are often thought of strictly in the geopolitical sense, that is, the borders that are visible on maps, globes, and atlases. These borders are depictions of state sovereignty, established where states’ lines, and power, exist. Often, states seek to expand their power beyond their borders through colonization, invasion, annexation, and the like.

The study of borders is dominated by the discourse of power and power dynamics, as seen in the ways that borders have continuously been militarized and securitized in Canada, the US, the European Union, and in occupied Palestine. Today, borders are utilized as displays of power but also exist as sites of violence, manifesting not just at the edges of states but in the everyday lives of immigrants and citizens alike.6 Borders, and who’s home in them, as well as who is outside of them, are set by those with the most power. Sometimes this is the state itself, but often it is the presumed hegemonic norm of those within the state namely white, heterosexual, able-bodied, citizens. There is often a fear of those who do not fit in well, or who disrupt, the norm. Those who may straddle, resist, or ignore borders are often seen, and portrayed as, threatening and in need of being policed.7

Borders Beyond the Geopolitical

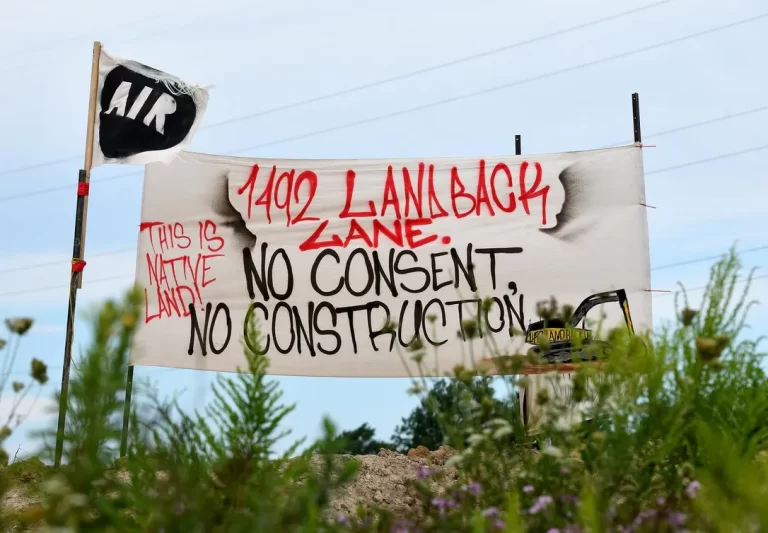

Indigenous Peoples’ Realities of Borders: The Border Crossed Us

Indigenous people’s histories, identities, and rights span and regularly confound the borders constructed by colonial nation states. In different ways, First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people all have histories and territories spanning Canada’s northern or southern borders. Rights, like those claimed under the Jay Treaty of 1794 speak to these histories, as does the persistence of host laws as described by scholar, author, and poet Lee Maracle, member of the Stó:lō First Nation8, or the insistence of First Nations like the Haudenosaunee to travel under their own passports. For all of this, the nation states of setter colonial societies loom large in Indigenous pasts and presents.

Indigenous people have been refugees and migrants in different settler states. While being dispossessed from their lands and often displaced, they have also resisted that displacement and fought for and claimed rights and recognition from nation states, and from colonial authorities and governments including governance of their lands within existing states like the territory of Nunavut. Worldwide, Indigenous peoples have defended their rights to exercise sovereignty within the borders and across borders and have created new institutions and laws such as the Te Tiriti o Waitangi (and its current translation into Māori law), the Sami Parliament, as well as the Universal Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and its ongoing implementation into domestic and international law.

Identity and Borders

Identity, and needing to “prove” one’s membership to a particular group for purposes of safety, rights-claiming, and protection, is also an obstacle that many face. One needs to prove, often to an external being using external rubrics, their identity and thus their belonging. It is often a rigid system based on the logic of the state and/or those in power and any ambiguity is viewed as suspect. This is most clearly seen in the colonial definitions of Indigeneity under Canada’s Indian Act, but also in refugee claims, in the state’s responses to people who identify as Two-Spirit/LGBTQ+, and in the racial dynamics involved with Canadian immigration policies and programs.

“The world, which is the private property of a few, suffers from amnesia. It is not an innocent amnesia. The owners prefer not to remember that the world was born yearning to be a home for everyone.”

— Eduardo Galiano

Gender, the Body, and Borders

Gender can be understood as a shifting border, as well as a factor that contributes to real difficulties in crossing geopolitical borders.

For many communities throughout the world, including in many Indigenous communities in Canada, gender is seen along a continuum, with space and acceptance for gender fluidity. Colonialism imposed artificial gender binaries with “two very clear genders: male and female and it lays out two very clear sets of rigidly defined roles based on colonial conceptions of femininity and masculinity.”9 Colonialism imposed colonial gender roles to replicate the heteronormative and patriarchy of western societies. In Canada, this meant that matriarchal systems of power were disregarded and members of the Two-Spirit/LGBTQ+ community are marginalized, erased and/or feared, too often resulting in discrimination, criminalization, and at times violence.

Gender also influences economic outcomes, as well as the access that individuals have over resources and services such as healthcare and education, and interplays with other social locations such as race and citizenship.

Borders of Virtue: “Good migrant” and “Bad migrant”

Borders, and the practice of bordering, are not limited to the geopolitical borders that exist between states. The discourse of the worthy versus the unworthy migrant is ever-present in the contemporary west. This is largely seen in the division between refugee (political) and immigrant (economic) with host states creating a false distinction between politics and economics and based on the needs, priorities, and loyalties of the state, labelling various migrant groups as worthy or unworthy, and skilled or unskilled, respectively. The migrants that will economically benefit the host state are established as “good” while “bad” migrants are regarded as burdens and often given precarious or temporary status.10 The refugee may be seen as worthy of humanitarian assistance, while the immigrant is overlooked and their experience of crossing borders – both state borders and borders within the immigration system – is complicated. However, this is not always true as some refugees can be regarded as a “bad” migrants, particularly if they exercise their right to enter a country irregularly.

Borders and Race

Race has been a determining factor in Canada’s immigration policies and programs since Confederation. Defining who counts as a ‘good’ migrant or a ‘bad’ migrant, certain racial and ethnocultural groups were granted entry to Canada as settlers while “others” faced legislation limiting their entry.11 Upon migrating to Canada, people of color are often racialized and are expected to assimilate into Canadian society by losing their ethnocultural markers, as seen in hijab bans across the world, including Quebec’s Bill 21. Along with gender, race has historically played a fundamental role in defining access to resources and services, with racial hierarchies being systemically ingrained within today’s institutions and structures. Both settler and extractive colonial projects utilized race as a way to segment populations through various legislative mechanisms including citizenship. Today, race is apparent in Canada’s immigration policies and programs, where racialized individuals are more likely to be granted precarious citizenship status as temporary workers and international students. Race also plays a role in the homogenization and racialization of Indigenous peoples in Canada.

Borders, Economies, and Goods

People are not the only thing that moves across borders. The global supply chain explains the movement of goods – or the failure – within and between countries, often along lines created by imperialism and globalization. The notion of the global supply chain and the movement of goods across borders demonstrates the relationship between goods and people: when people do not have what they need to survive, they will move to find it. This is clearly seen in the increasing effects that climate change is having in terms of agricultural, pastoral and fishing societies. Since the prolific increase in globalization (and homogenization of goods) more people are moving to urban centres or abroad because their traditional livelihoods are no longer viable. This increase of movement of people into highly centralized areas and away from one’s land often because they are no longer able to be self-sustaining is a result of, and at times leads to, human rights violations.12

In addition, one can see that the right to health, food, water and shelter is not distributed equally – a clear violation of international human rights law. This has been demonstrated recently by the consistent but changing ruptures in the supply chain during the COVID-19 pandemic; including because of travel restrictions, restrictions in shipping, political blockades of borders, and health restrictions and mandates. In addition, the unequal distribution of COVID-19 vaccines (because of its treatment as a commodity that must be regulated through borders rather than a universal necessity) has had significant effects on people worldwide. This could be most clearly seen when India, a worldwide distributor of COVID-19 vaccines, was unable to ensure its own population could be widely vaccinated because it had made commitments to the global market.

Within economies around the globe, migrant workers have played a fundamental role in filling labour demand in countries such as Canada. Canada continues to depend on temporary migrant work in its service, care, and agricultural sectors today, similar to how it depended on Chinese workers in the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway.13 However, these workers, who are often racialized and gendered, face barriers to permanent residence, access to public services such as healthcare, and other economic opportunities. Migrant workers thus face the duality of being essential to the Canadian economy, but are deemed disposable through the lack of supports and protections available to Canadian citizen-workers.14

Struggles Against Borders

Borders are not simply a method of self-determination; they rarely create autonomy or freedom, and they do not tend to enhance human rights. Borders are mainly carceral; they can be used to punish, to regulate, and to restrict land, and bodies, and people’s mobility all around the world.

Borders and colonialism are mutually constitutive15 and as such, so are the struggles against them. In the context of CHRR’s work in support of Indigenous sovereignty, to struggle against borders is also to struggle against colonialism in the work for a more just future.

1Razack, Race, Space, and the Law.

2Walia, “There Is No ‘Migrant Crisis’”; Walia, Border and Rule.

3Walia and Wilson, “The Centre for Human Rights Research Critical Conversations: Talking Borders, Colonialism, Resistance, and Human Rights.”

4Craft and Olivares, “Trump drives surge in Ice detentions,” The Guardian.

5Cole, “Carney’s border bill is a gift to Trump,” The Breach

6Yuval-Davis, Wemyss, and Cassidy, “Everyday Bordering, Belonging and the Reorientation of British Immigration Legislation.”

7Aliverti, “Introduction.”

8Maracle, “May Day Assembly”; Maracle, My Conversations with Canadians.

9Simpson, “Not Murdered and Not Missing.”

11Abu-Laban, Tungohan, and Gabriel, Containing Diversity: Canada and the Politics of Immigration in the 21st Century.

12Tacoli, McGranahan, and Satterthwaite, “World Migration Report 2015: Urbanization, Rural–Urban Migration and Urban Poverty,” 3.

13Tungohan, “Contextualizing Care Activism”; Fernandez, Read, and Zell, “Migrant Voices: Stories of Agricultural Migrant Workers in Manitoba.”

14Henaway, Essential Work, Disposable Workers: Migration, Capitalism, and Class.

15Walia and Wilson, “The Centre for Human Rights Research Critical Conversations: Talking Borders, Colonialism, Resistance, and Human Rights.”

References

Abu-Laban, Yasmeen, Ethel Tungohan, and Christina Gabriel. Containing Diversity: Canada and the Politics of Immigration in the 21st Century. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2022.

Aliverti, Ana. “Introduction: Special Issue on ‘Policing, Migration and National Identity.’” Theoretical Criminology 24, no. 1 (February 1, 2020): 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480619898015.

Cole, Desmond. “Carney’s border bill is a gift to Trump—And a roadmap to ‘mass deportation.’” The Breach, June 13, 2025, https://breachmedia.ca/carneys-border-bill-gift-to-trump-and-roadmap-to-mass-deportation/

Craft, Will and José Olivares. “Trump drives surge in Ice detentions.” The Guardian, June 24, 2025. www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/jun/24/trump-immigrants-ice-arrests.

Fernandez, Lynne, Jodi Read, and Sarah Zell. “Migrant Voices: Stories of Agricultural Migrant Workers in Manitoba,” 2013. www.migrantworkersrights.net/en/en/resources/migrant-voices-stories-of-agricultural-migrant-work.

Henaway, Mostafa. Essential Work, Disposable Workers: Migration, Capitalism, and Class. Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing, 2023.

Maracle, Lee. “May Day Assembly.” Presented at the No One is Illegal, Vancouver, BC, 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FNK3KDfMrRc&t=55s.

———. My Conversations with Canadians. Essais, v. 4. Toronto: BookThug, 2017.

Razack, Sherene, ed. Race, Space, and the Law: Unmapping a White Settler Society. Toronto: Between the Lines, 2002.

Simpson, Leanne. “Not Murdered and Not Missing.” NM Media Co-Op (blog), March 17, 2014. https://nbmediacoop.org/2014/03/17/not-murdered-and-not-missing/.

Stasiulis, Daiva. “Elimi(Nation): Canada’s ‘Post-Settler’ Embrace of Disposable Migrant Labour.” Studies in Social Justice 14, no. 1 (2020): 22–54. https://doi.org/10.26522/ssj.v2020i14.2251.

Tacoli, Cecilia, Gordon McGranahan, and David Satterthwaite. “World Migration Report 2015: Urbanization, Rural–Urban Migration and Urban Poverty.” London: International Organization for Migration, 2014. https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl2616/files/2018-07/WMR-2015-Background-Paper-CTacoli-GMcGranahan-DSatterthwaite.pdf.

Tungohan, Ethel. “Contextualizing Care Activism.” In Care Activism: Migrant Domestic Workers, Movement-Building, and Communities of Care, 19–62. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2023.

Walia, Harsha. Border and Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism. Fernwood Publishing, 2021. https://fernwoodpublishing.ca/book/border-and-rule.

———. “There Is No ‘Migrant Crisis.’” Boston Review, November 16, 2022. https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/there-is-no-migrant-crisis/.

Walia, Harsha, and Alex Wilson. “The Centre for Human Rights Research Critical Conversations: Talking Borders, Colonialism, Resistance, and Human Rights.” Presented at the Critical Conversations, Virtual, February 17, 2023. https://chrr.info/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Walia-Wilson-Bios.pdf.

Yuval-Davis, Nira, Georgie Wemyss, and Kathryn Cassidy. “Everyday Bordering, Belonging and the Reorientation of British Immigration Legislation.” Sociology 52, no. 2 (April 1, 2018): 228–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038517702599.

Resources

To learn more about borders and human rights, check out this reference guide compiled by Sara Gibson.

Affiliate Researchers

Related Resources

Explore More Research Themes

-

Water Rights & Justice Theme

FIND OUT MORE -

Indigenous Peoples & Human Rights Theme

FIND OUT MORE -

Reproductive & Bodily Justice Theme

FIND OUT MORE -

History & Commemoration Theme

FIND OUT MORE

Support Us

Whether you are passionate about interdisciplinary human rights research, social justice programming, or student training and mentorship, the University of Manitoba offers opportunities to support the opportunities most important to you.