By: Kiersten Sanderson (she/they)

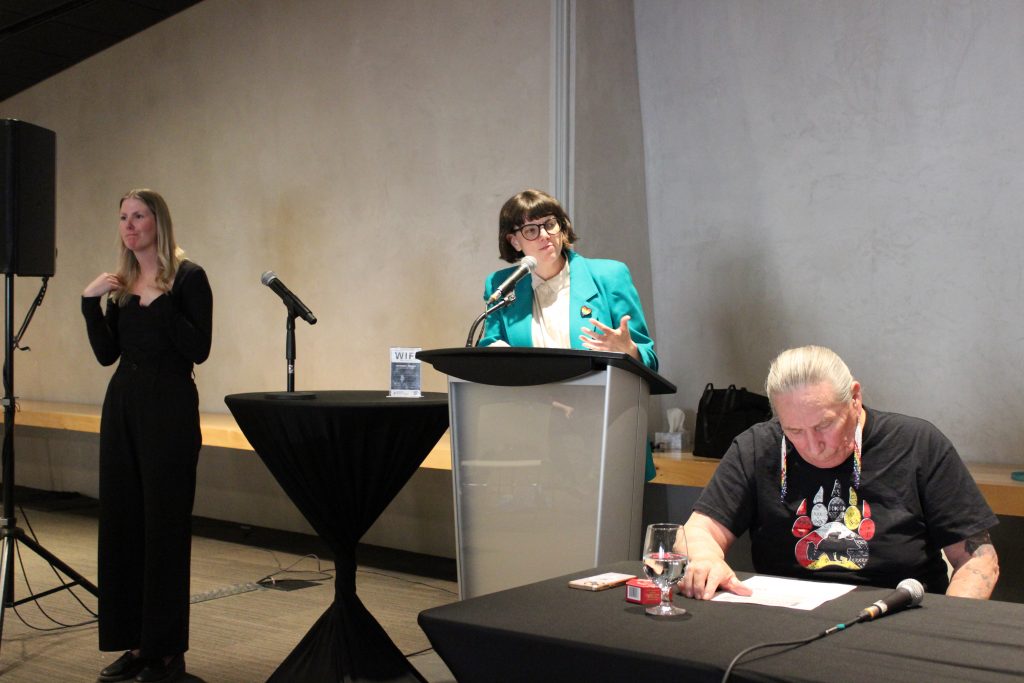

‘Water and Climate Justice: Advancing Intersectional Approaches’, was held on May 27-28th, 2024 at the University of Manitoba. With funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, it was led by Dr. Nicole J. Wilson, Assistant Professor in Environment and Geography and Research Affiliate with the Centre for Human Rights Research. This workshop was supported by the Centre for Human Rights Research, Centre for Earth Observation Science, Decolonizing Water, the UBC Program on Water Governance, and the Household Water Insecurity Experiences (HWISE) – Research Coordination Network. The workshop culminated in an engaging panel on the evening of the May 28th at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights.

Images: Nick Lupky.

The workshop gathered some of the most incredible and inspiring individuals – scholars, activists, advocates, storytellers – all of whom work in the realm of water and climate justice. An important goal of the two-day workshop was bridging the gap and uniting the diverse disciplines that work on water scholarship. For me, it was this diversity amongst scholars and practitioners represented just how integral the issue was. Many had a background in natural sciences, however there were just as many with humanities and social sciences backgrounds, including history, literature, and governance. A notable observation was that most attendees were women. There was a strong influence and respect towards Indigenous ways of knowledge and philosophies.

I joined the workshop as a Student Research Assistant at the CHRR, working on the newly funded Just Waters project. I was selected as a Research Assistant as part of the Indigenous Summer Student Internship Program. For me, it felt good to return to water justice – to a topic that I’ve always felt passionate about. I’m a part of a generation that has grown up with climate change, water injustices, and inequities all being topics in the curriculum. Throughout high school, I actively participated in our environmental justice student group, which included biannual water testing and sampling at three different sites. Because of my disinterest in the natural sciences, I never considered that I would be able to continue with my interests in academia; the workshop provided me with a chance to meet scholars and professionals who come at the issue from diverse disciplines and perspectives.

Following introductions, together the attendees established themes of knowledge gaps that required further discussion. These four themes included:

- Justice Frameworks

- Procedural Justice

- Unity of Knowledge

- Well-being

This opening exercise was eye-opening. These areas of study don’t exist within silos, the way that we might perceive them to. These issues are as much of social ones as they are scientific. While I might be currently pursuing a career in the legal field there are still ways I can advocate for climate and water justice. There is work to be done, regardless of the educational background one might have. Everyone has a role and a responsibility when it comes to water, and the participation of everyone is integral for our future.

In the months following the workshop, I found myself thinking often of one theme that had been identified by the group – unity of knowledge. The idea was to explore how different areas of study operate in silos, and they remain separate and distinct, with little overlap or little collaboration. This is true for not only the natural sciences and humanities/social sciences, but also western knowledge on water and Indigenous knowledge systems on water. It’s important to integrate all the different forms of knowledge together. This includes how to integrate the natural sciences together with concepts of justice.

I’ve also been thinking back to my participation in water testing in high school at Whitemud River, Manitoba. While testing the water – we considered questions related to the appearance of water and the recreational usage of the water. At one of the sites, a few students shared that they had swam in the water for years; yet there were many of us who hadn’t even considered this water as being suitable for swimming because of the way we perceived the conditions of the water and the surrounding environment. Within the group, we had different relationships with the water. This is an important attribute to the data we collected. While the tests that we would conduct may provide data about whether the water was good for recreational usage, this is in a context where people had ongoing relationships with that water, and different opinions on what makes the water safe for recreational usage. If the results either we or the lab found it to be unsafe, the cause of the problem could be dealt with. The community could also be made aware so they can make decisions for their well-being. Both the tests we conducted, and the information provided by those with ongoing relationships to the site were valuable to the data we collected.

When we think about bridging these silos, it can happen during water testing. When you go out to collect water samples, the testing could also involve questions about your relationship to the water, or questions rooted in Indigenous ways of knowing. This could include asking those taking samples to consider how the condition of the water makes you feel, to document animals that you might’ve seen, or to answer whether you might swim or drink the water. To me, these questions make sense especially when members that are collecting water samples are a mix of those local to the area and those who are not.

Our relationships to water and the various forms of knowledge about water are all important in addressing the complex challenges of water and climate injustices that we face today. The workshop helped me return to my passion. Climate and water justice need to transition to both prioritizing interdisciplinary work and also valuing and respecting Indigenous knowledge (as much as western science typically is) if we are to address the complexities of water injustices.