University of Manitoba Period Supply Access Map

October 18, 2025

Centre for Human Rights Research

As a part of CHRR’s Period Poverty and Equity, On Campus and Beyond project, a team of volunteers conducted an audit of washrooms on the University of Manitoba campus to assess the availability of period supplies. The audit found that period supplies were freely available in less than 3% of the washrooms on campus. Many of the coin-operated dispensers that did exist in many of the bathrooms were empty or malfunctioning. At the time of the audit, there were no period supplies in any men’s washrooms on campus.

In September 2025, the University of Manitoba, with the guidance of UMSU Women’s Centre, increased the availability of free period supplies on campus with baskets in a number of washrooms (including women’s, men’s, gender inclusive, and accessible washrooms) across campus. With the support of Caretaking Services, the baskets will include a form with a QR code with a request to be filled.

Our map features a list of places to access period supplies on the University of Manitoba campuses was created to help promote equitable access to period supplies for menstruating individuals at the university.

“Period Poverty and Equity, on Campus and Beyond” utilized a menstrual justice lens to bring together faculty and staff, with students and organizations, to address period poverty (the increased economic vulnerability resulting from the financial burden posed by the need for menstrual supplies) and promote period equity.

If you know any additional places to access period supplies on the University of Manitoba campus, please contact us at chrr@umanitoba.ca.

Legend

Locations with period supply in washrooms

Non-washroom locations with period supplies

Fort Garry Campus

Active Living Centre, Room 159 (women’s), Room 158 (men’s), Room 345A (gender inclusive), Room 234 (gender inclusive), Room 254 (gender inclusive)

Agriculture, Room 124 (women’s), Room 167 (women’s)

Agriculture Lecture Block, Room 202A (women’s)

Allen, Room 304A (women’s), Room 531 (women’s), Room 101A (women’s), Room 103 (men’s)

Animal Sciences, Room 144A (women’s), Room 234C (women’s)

Architecture 1 (Russell), Room 309 (women’s), Room 109A (women’s)

Architecture 2, Room 202 (women’s), Room 303 (women’s)

Armes, Room 104 (women’s/accessible), Room 108 (men’s), Room 106A (gender inclusive/accessible)

ARTlab, Room 353 (women’s), Room 352 (men’s), Room 453 (women’s), Room 166 (women’s)

ASBC Health and Wellness Centre*, Faculty of Arts Student Lounge, Fletcher Argue Building

Biological Sciences, Room 107 (women’s), Room 403B (women’s)

Buller, Room 218B (women’s), Room 218A (gender inclusive), Room 415 (women’s)

Centre for Human Rights Research*, 4th Floor Robson Hall

Chancellors Hall, Room 102 (women’s), Room 103 (men’s)

Dairy Science, Room 204B (gender inclusive)

Drake, Room 149 (gender inclusive), Room 274 (gender inclusive), Room 337 (gender inclusive), Room 527 (gender inclusive)

Duff Roblin, Room 201 (women’s), Room 203 (men’s), Room 303 (women’s), Room N316 (women’s), Room 401 (women’s), Room 403B (gender inclusive)

Education, Room 218 (gender inclusive), Room 219 (gender inclusive), Room 332 (women’s), Room 330A (gender inclusive), Room 292 (gender inclusive)

Elizabeth Dafoe Library, Room 105 (women’s), Room 108W (gender inclusive), Room 211 (gender inclusive), Room 214 (gender inclusive), Room 320 (women’s)

Ellis, Room 214W (women’s)

Engineering E1, Room E1-204 (gender inclusive), Room E1-292 (gender inclusive)

Engineering E2, Room E2-347 (women’s), Room E2-151 (men’s), Room E2-141 (women’s), Room E2-247 (women’s), Room E2-547 (women’s)

Extended Education, Room 164 (gender inclusive)

Frank Kennedy, Room 130B (gender inclusive), Room 130C (gender inclusive), Room 317A (gender inclusive), Room 317B (gender inclusive), Room 159A (gender inclusive), Room 152A (gender inclusive)

Helen Glass, Room 139 (women’s), Room 273 (women’s), Room 204 (gender inclusive), Room 339 (women’s), Room 314 (gender inclusive), Room 439 (women’s)

Human Ecology, Room 116A (women’s), Room 116B (men’s), Room 319/320 (gender inclusive), Room 414 (gender inclusive)

Fletcher Argue, Room 101C (gender inclusive), Room 211B (women’s), Room 211A (men’s), Room 121 (gender inclusive)

Investors Group Athletic Centre, Room 126 (men’s), Room 128 (women’s), Room 321 (women’s),

Isbister, Room 132 (women’s), Room 134 (men’s), Room 135 (gender inclusive), Room 337A (gender inclusive)

Machray Hall*, Room 204 (women’s/accessible)

Max Bell Centre, Room 121 (women’s), Room 202 (women’s), Room 101 (women’s)

Migizii Agamik* (gender inclusive, men’s, and women’s)

Parker, Room 106B (women’s), Room 409A (women’s)

Pembina Hall, Room 110A (women’s), Room 109 (men’s), Room 115 (gender inclusive)

Robert B. Schultz Theatre, Room 162 (women’s), Room 165 (men’s)

Robson Hall, Room 105C (women’s), Room 203C (gender inclusive), Room 203D (gender inclusive), Room 408 (women’s)

Sinnott, Room 326 (women’s)

Stanley Pauley Engineering, Room SP118 (women’s), Room SP117 (gender inclusive)

St. John’s College, Room 122 (women’s)

St. Paul’s College, Room 156 (women’s), Room 158 (men’s)

Student Wellness Centre*, 162 Extended Education

Tache 2, Room T2-235 (gender inclusive)

Tache Arts Complex, Room 116A (gender inclusive/accessible), Room 116C (gender inclusive), Room 264A (gender inclusive), Room 264B (gender inclusive), Room 316 (gender inclusive/accessible), Room 416 (gender inclusive/accessible), Room 446A (gender inclusive), Room 446B (gender inclusive), Room 464A (gender inclusive), Room 464B (gender inclusive)

Tier, Room 112 (women’s), Room 102 (men’s), Room 211B (gender inclusive), Room 309A (women’s), Room 412A (women’s)

UMSU University Centre, Room 110E (gender inclusive), Room 110B (gender inclusive), Room 110C (men’s), Room 110F (women’s), Room 133 (gender inclusive), Room 127 (men’s), Room 131 (women’s), Room 231 (women’s/accessible), Room 307 (women’s), Room 307 (women’s), Room 506 (women’s), Room 506A (women’s)

UMSU Women’s Centre*, 190 Helen Glass

University College, Room 134A (women’s), Room 135D (men’s)

Wallace, Room 225A (gender inclusive), Room 225B (gender inclusive), Room 225C (gender inclusive), Room 200A (gender inclusive), Room 200B (gender inclusive), Room 204 (gender inclusive)

Welcome Centre, Room 106 (gender inclusive)

Richardson Centre, Room 166 (women’s), Room 167 (men’s)

*Areas with an asterisk are not maintained or replenished by Physical Plant. Please contact the respective groups to replenish these supplies.

Bannatyne Campus

Apotex Centre, Room 102 (women’s), Room 202 (women’s)

Basic Medical Science, Room 151 (women’s),Room 228 (women’s)

Chown Building*,1st floor (men’s and women’s)

Dentistry, Room D215 (women’s), Room D013A&B (women’s)

Medical Services, Room S209A (women’s)

Med Rehab, Room R150 (women’s)

Pathology, Room P307 (gender inclusive)

*Areas with an asterisk are not maintained or replenished by Physical Plant. Please contact the respective groups to replenish these supplies.

William Norrie Centre

Environmental Impact of Period Management Options

Environmental Impact of Period Management Options

May 31, 2024

Chloe Vickar (she/her)

Image: Ebunoluwa Akinbo

Although period management options have improved significantly in the last half century, there is still work to be done to improve period products for the well-being of those who use them, and the well-being of the environment. As we work towards implementing menstrual justice in our communities, we must also prioritize the environmental cost of menstruating.

The environmental impact of period products can be measured by looking at the use of raw materials, energy, and water during the manufacturing processes, the makeup of the components of the products (plastic versus cotton, for example), the packaging of the products, and the total quantity of how many products are used and disposed of globally. However, there is little available literature on the exact environmental impact of disposable period products.

In addition to pads, tampons create significant waste. In the United States, approximately 12 billion pads and 7 million tampons are used each year. The plastic applicators are often marketed as recyclable; however, these pieces are rarely actually recycled. The presence of blood/organic matter disqualifies the applicators from being eligible to recycle in most jurisdictions. Further, as much as 400 pounds of packaging from period products is discarded for each person that menstruators in their lifetime.

Many reusable period products are available as alternatives to disposable pads and tampons. Menstrual cups, discs, reusable pads, and period underwear are among the most popular. Cups and discs are worn internally and made of medical grade silicone, or other body-safe ingredients like TPE, and can be washed and reused for up to 10 years, depending on the brand and the user. In addition to their environmental benefits, cups and discs often hold more menstrual blood than pads and tampons. There are many options for shape, size, and capacity, depending on the menstruator’s anatomy and flow.

Period underwear is increasing in popularity in recent years. It features an absorbent gusset and can be washed and reused for years. Period underwear often holds less menstrual blood than cups or discs but can be worn as backup for leaks in addition to an internal product, or by itself during spotting or for those with a light flow.

There are options for disposable pads and tampons that have lighter environmental footprints than plastic-based products. Pads and tampons made of cotton are healthier for the person using them and for the environment.

Reusable products are not suitable for all bodies, lifestyles, and circumstances, for example due to lack of resources, education, or personal preference. While reusable period products can last many years, they have higher upfront costs than disposable products. Further, internal reusable options such as cups and discs may not work well for all bodies, as each menstruator has different preferences based on their individual needs. Reusable pads are a great option for reducing waste, however one must be able carry the used pad with them until they can be laundered. Therefore, healthier disposable options made from organic cotton are important.

This savings calculator from Winnipeg-based reusable period product company Tree Hugger Cloth Pads illustrates financial and environmental savings from switching to reusable cloth pads.

Environmental impact must be taken into consideration when conceptualizing period products, however disposable options continue to be necessary. The waste associated with disposable products cannot be used as an argument to discourage the importance of free period products. We can advocate for accessibility of products, including disposable and reusable products, so that all menstruators have safe and reliable products.

For more information about the environmental impact of period products, check out these resources:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/wellness/2023/09/12/period-products-absorption-study-blood

Hand, J., Hwang, C., Vogel, W., Lopez, C., & Hwang, S. (2023). An exploration of market organic sanitary products for improving menstrual health and environmental impact. Journal of Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene for Development, 13(2), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2023.020

Harrison, M. E., & Tyson, N. (2023). Menstruation: Environmental impact and need for global health equity. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 160(2), 378–382. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.14311

https://www.treehuggerclothpads.com

https://www.treehuggerclothpads.com/pages/savings-calculator

May 28th is menstrual hygiene day, and this year, the theme is “Together for a #PeriodFriendlyWorld.” While this observance was originally framed as menstrual hygiene – we follow the lead of the World Health Organization, who calls for menstrual health to be recognized, framed, and addressed as a human rights issue, not a hygiene issue. Framing menstruation as such is a reflection of the taboo and stigma around periods. The labelling of period supplies as “feminine hygiene products” is incorrect since as Dr. Jen Gunther explains “needing them is not a sign of being feminine – it’s a sign that you need something to catch blood – and they’re not hygiene products because menstruating is not unhygienic.”

In 2023-2024, the Centre for Human Rights Research at the University of Manitoba has worked on the “Period Poverty & Equity, On Campus and Beyond” project to assess access to period supplies for the University of Manitoba community and to work towards menstrual equity, on campus and in the community. This series of essays is part of the Period Poverty & Equity, On Campus and Beyond project and aims to explore issues of menstrual justice that are often overlooked.

Menstruation and Gender: Beyond Cisgender

Menstruation and Gender: Beyond Cisgender

May 28, 2024

Mikayla Hunter (she/they)

Image by Mikayla Hunter

It is not only cisgender women who menstruate. For some, this idea may be something they are already aware of and understand to be true. For others, it may be a little more difficult. To understand that menstruation is not an experience specific to women, we must first understand what we mean by gender.

The term cisgender refers to a person whose gender identity aligns with the sex they were assigned at birth.1 Transgender is a term for people whose gender identity does not align with the sex they were assigned at birth.1 It is important to note that both ‘cis’ and ‘trans’ are simply prefixes that add additional information to a word or an idea, and neither of these terms are slurs. For example, we can refer to a book as a hardcover book to give more information about the book that we are talking about. Cis is a prefix that means ‘on the same side as’ and trans means ‘on the other side of’. This means that a cisgender woman is a woman whose gender identity is ‘on the same side as’ the sex she was assigned at birth. A transgender man is a man whose gender identity is ‘on the other side of’ the sex he was assigned at birth. With these ideas in mind, we can understand that both cisgender women and transgender men may have a uterus and experience menstruation. However, it is not just cisgender women and transgender men who may have these experiences.

Gender diverse people have a wide range of gender identities and/or gender expressions that do not conform to socially defined gender norms of men and women.2 There are many terms and identities that people may use to describe themselves including non-binary, agender, genderqueer, and gender non-conforming to name a few. Gender diversity does not look a specific way, and the experiences of gender diverse people can (and do) vary. For example, not every gender diverse person will dress androgynously and not all of them will experience menstruation. However, some of them will. Similar to how both cisgender women and transgender men can experience menstruation, so can gender diverse people. A person who menstruates doesn’t look any one specific way or identify as a woman.

Importantly, menstruation can cause gender dysphoria for transgender and gender diverse people. Gender dysphoria is the experience of discomfort or distress because there is a mismatch between a person’s sex assigned at birth and their gender identity.3 For some transgender and gender diverse people, they may undergo procedures such as hysterectomy to relieve gender dysphoria and as a part of their gender journey. However, not everyone has access to these surgical procedures for a variety of reasons and so, menstruation can be all the more difficult for transgender and gender diverse people.

Femininity and menstruation do not go hand-in-hand. A person’s gender identity is their internal sense of gender, or lack thereof. The biological function of our bodies is not directly tied to our gender identities. And so, saying that only women menstruate is incorrect. As Kimberlé Crenshaw explains,4 when policies that support women only support women and policies that support Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour (BIPOC) people only support BIPOC men, BIPOC women are not supported by either policy. When we consider the idea of menstrual equity, we need to ensure that all bodies that menstruate are included and not just cisgender women. Otherwise, we haven’t achieved menstrual equity at all if people are being left out of advocacy and policy changes.

References

[1] Rainbow Center. (2018). Rainbow Center’s LGBTQIA+ dictionary. The University of Connecticut.

[2] https://www.dictionary.com/browse/gender-diverse

[3] https://www.stonewall.org.uk/list-lgbtq-terms

[4] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ViDtnfQ9FHc

May 28th is menstrual hygiene day, and this year, the theme is “Together for a #PeriodFriendlyWorld.” While this observance was originally framed as menstrual hygiene – we follow the lead of the World Health Organization, who calls for menstrual health to be recognized, framed, and addressed as a human rights issue, not a hygiene issue. Framing menstruation as such is a reflection of the taboo and stigma around periods. The labelling of period supplies as “feminine hygiene products” is incorrect since as Dr. Jen Gunther explains “needing them is not a sign of being feminine – it’s a sign that you need something to catch blood – and they’re not hygiene products because menstruating is not unhygienic.”

In 2023-2024, the Centre for Human Rights Research at the University of Manitoba has worked on the “Period Poverty & Equity, On Campus and Beyond” project to assess access to period supplies for the University of Manitoba community and to work towards menstrual equity, on campus and in the community. This series of essays is part of the Period Poverty & Equity, On Campus and Beyond project and aims to explore issues of menstrual justice that are often overlooked.

Indigenous struggles toward period equity

Indigenous struggles toward period equity

May 29, 2024

Bethel Alemaio (she/her)

Image: Money is Cheaper, Period. By Lauren C.

Many Canadians struggle to gain equitable access to menstrual products. Plan International Canada’s Menstruation in Canada Views and Realities reveals the consequences of unaffordable and inaccessible menstrual products among youth and adults. One in five (22%) of the respondents ration their products, and this number rises to 33% for those with household incomes less than $50,000 (Plan International Canada 2022). A recent report focusing on menstrual needs in northern communities noted that 74% of Indigenous respondents in remote communities and 55% of Indigenous respondents in non-remote communities “sometimes” or “often” have issues accessing menstrual products (Lane 2024). Resulting from this, in recent years, Indigenous leaders nationally have fought for easier access to period products (Toory 2022).

Sol Mamakwa, MPP of northern Ontario, is one such person. In 2021, after Shoppers Drug Mart announced its plan to donate menstrual products to public schools, 120 federally funded First Nations schools were excluded from this distribution. Mamakwa was outspoken about the province’s discriminatory practices, which violated Jordan Principle. Within this policy, it is mandated that the needs of First Nations Children to access “products, services, and supports” (Indigenous Services Canada, 2024) requires the collaboration of both the federal and provincial governments in a timely manner. Mamakwa further indicates his disappointment as the products were a private donation and did not require the spending of provincial funding.

Moon Time Connections, a national organization dedicated to providing menstrual products to Indigenous peoples throughout Turtle Island, shares Mamakwa’s concern. Working with the Ontario chapter of Moon Time Connections, Veronica Brown recognizes the government’s actions as a “colonial barrier” (McGillivray 2021) to equitable access to period products.

Nichole White created Moon Time Connections because she discovered Indigenous students learning in remote and rural areas were missing school due to a lack of access to menstrual products. The first chapter was created in Saskatchewan, previously known as Moon Sisters, and the organization expanded to Ontario, Manitoba, and British Columbia. They actively work toward period equity in collaboration with 120 northern Indigenous Communities from coast to coast.

References

Lane, Heather. 2024. “An Assessment of Menstrual-Related Needs in Northern Communities.” Moon Time Connections. True North Aid. https://truenorthaid.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/An-Assessment-of-Menstrual-Related-Needs-in-Northern-Communities-FINAL.pdf.

McGillivray, Kate. 2021. “MPP Calls out Province’s Free Menstrual Products Plan for Not Including First Nations Schools.” CBC News, October 23, 2021. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/mpp-calls-out-province-s-free-menstrual-products-plan-for-not-including-first-nations-schools-1.6219813.

Plan International Canada. 2022. “Menstruation in Canada – Views and Realities.” Plan International. https://www.multivu.com/players/English/9052951-menstrual-health-day-2022/docs/ViewsandRealities_1653434611799-556425632.pdf.

Toory, Leisha. 2022. “Menstrual Health Is a Public Health Crisis for Indigenous Youth.” Toronto Star, October 13, 2022. https://www.thestar.com/opinion/contributors/menstrual-health-is-a-public-health-crisis-for-indigenous-youth/article_d8f3098b-1a61-52b7-a9c1-a8bdb9dc926d.html.

May 28th is menstrual hygiene day, and this year, the theme is “Together for a #PeriodFriendlyWorld.” While this observance was originally framed as menstrual hygiene – we follow the lead of the World Health Organization, who calls for menstrual health to be recognized, framed, and addressed as a human rights issue, not a hygiene issue. Framing menstruation as such is a reflection of the taboo and stigma around periods. The labelling of period supplies as “feminine hygiene products” is incorrect since as Dr. Jen Gunther explains “needing them is not a sign of being feminine – it’s a sign that you need something to catch blood – and they’re not hygiene products because menstruating is not unhygienic.”

In 2023-2024, the Centre for Human Rights Research at the University of Manitoba has worked on the “Period Poverty & Equity, On Campus and Beyond” project to assess access to period supplies for the University of Manitoba community and to work towards menstrual equity, on campus and in the community. This series of essays is part of the Period Poverty & Equity, On Campus and Beyond project and aims to explore issues of menstrual justice that are often overlooked.

Access to Menstrual Products in Federally Regulated Prisons in Canada

Access to Menstrual Products in Federally Regulated Prisons in Canada

May 30, 2024

Hannah Belec (she/her)

Image: iStock Photo

In December 2023, Employment and Social Development Canada announced that federally regulated employers must now provide pads and tampons to all employees in an accessible location at no cost. The press release from December 15th states that “menstruation is a fact of life” and pads and tampons are “basic necessities.”[1] Yet, current access to menstrual hygiene products in other federally regulated institutions, specifically prisons, certainly does not reflect the Canadian government’s apparent acceptance that “menstruation is a fact of life” and that both pads and tampons are “basic necessities.”[2]

In 2018, Public Safety Canada stated that there were approximately 676 federally incarcerated women.[3] These women make up between 7% and 8% of the total federal offender population and are the fastest-growing federal offender population.[4] For example, despite the total number of federally incarcerated offenders minimally increasing by 0.3% in the past ten years, the number of federally incarcerated women has increased by 20%.[5] Moreover, according to a 2022 study by Corrections Services Canada, there are approximately 21 openly trans-men and 17 individuals who openly identify as gender fluid, gender non-conforming/non-binary, intersex, two-spirited, or unspecified.[6] So, these statistics suggest that there are currently between 700 to 800 federally incarcerated offenders, residing in prisons designated for women and prisons designated for men, who may require menstrual hygiene products at some point during their incarceration, if not regularly – and this number will only continue to increase if the upward trend of federally incarcerated women continues.

In compliance with the United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-Custodial Measures for Women Offenders, or the Bangkok Rules, Canadian federal prisons provide “facilities and materials required to meet women’s specific hygiene needs, including sanitary towels provided free of charge.”[7] However, some prisons designated for women do not provide tampons free of charge, only pads. For example, in a 2017 report conducted by the Senate on womens’ experience in Canadian prisons, incarcerated women at Joliette Prison in Quebec stated that they had to purchase tampons from the canteen if they wanted them, as they were only provided one kind of sanitary pad.[8] The need to buy tampons is a barrier to menstrual equity in Canadian prisons despite the Canadian government stating that pads and tampons are a basic necessity.

Even if a Canadian prison provides both tampons and pads free of charge, many inmates complain that they are not provided enough. On average, menstruators use about 3-6 pads or tampons daily, so three tampons may not be enough for one day, depending on an individual’s flow.[9] Yet, one inmate participant in Dr. Martha Paynter’s reproductive justice workshop exclaimed, “Bring a box! Why don’t they bring a box? You ask for tampons, and they bring you three. We don’t want to ask the male staff for tampons.”[10] Another inmate participant stated that it was “degrading” to ask for more menstrual hygiene products.[11] For incarcerated trans-men and non-binary, two-spirit, or intersex offenders who menstruate, their reluctance to ask male or female staff for menstrual hygiene products is likely exacerbated by feelings of fear, shame, and gender dysphoria. So, all federally incarcerated offenders need free and easily accessible pads and tampons, just like federal employees, to ensure their menstrual hygiene needs are addressed, and their dignity or safety is not compromised.

These economic and gender-specific barriers to menstrual equity in Canadian prisons contradict the government’s assertion that “menstruation is a fact of life” and that both pads and tampons are “basic necessities.”[2] Just like employees of the federal government, all federally incarcerated offenders, in both prisons designated for men and prisons designated for women, need free and easily accessible pads and tampons. This International Women’s Day (March 8th) and Menstrual Hygiene Day (May 28th), let’s advocate for free and accessible menstrual hygiene products in federally regulated prisons alongside federally regulated workplaces – because offenders are humans with rights that must be protected.

References

[3] https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/ccrso-2018/ccrso-2018-en.pdf

[4] https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/cj-jp/state-etat/2021rpt-rap2021/pdf/SOCJS_2020_en.pdf

[5] https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/cj-jp/state-etat/2021rpt-rap2021/pdf/SOCJS_2020_en.pdf

[6] https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2022/scc-csc/PS83-3-442-eng.pdf

[8] https://sencanada.ca/en/sencaplus/news/life-on-the-inside-human-rights-in-canadas-prisons/

May 28th is menstrual hygiene day, and this year, the theme is “Together for a #PeriodFriendlyWorld.” While this observance was originally framed as menstrual hygiene – we follow the lead of the World Health Organization, who calls for menstrual health to be recognized, framed, and addressed as a human rights issue, not a hygiene issue. Framing menstruation as such is a reflection of the taboo and stigma around periods. The labelling of period supplies as “feminine hygiene products” is incorrect since as Dr. Jen Gunther explains “needing them is not a sign of being feminine – it’s a sign that you need something to catch blood – and they’re not hygiene products because menstruating is not unhygienic.”

In 2023-2024, the Centre for Human Rights Research at the University of Manitoba has worked on the “Period Poverty & Equity, On Campus and Beyond” project to assess access to period supplies for the University of Manitoba community and to work towards menstrual equity, on campus and in the community. This series of essays is part of the Period Poverty & Equity, On Campus and Beyond project and aims to explore issues of menstrual justice that are often overlooked.

Period Poverty and Equity Zotero Library

Period Poverty and Equity Zotero Library

May 29, 2025

Hannah Belec

As a part of the Period Poverty and Equity, on Campus and Beyond project, a Zotero library was created to aid in gathering and organizing resources related to the project. Zotero is a free, easy-to-use tool to help you collect, organize, annotate, cite, and share research.

To access the Zotero library, click here.

The creation of this library was a collaborative project. We are grateful to the research team, comprising Dr. Pauline Tennent, Dr. Adele Perry, Dr. Lindsay Larios, and Dr. Julia Smith, as well as the projector coordinator, Chloe Vickar, and student research assistants, Bethel Alemaio, Hannah Belec, Mikayla Hunter, and Victoria Romero for their work on this project.

Period Poverty and Equity, on Campus and Beyond is funded by the University of Manitoba Strategic Initiatives Support Fund, and with support from the Faculty of Arts, to bring together faculty and staff, with students and organizations, to address period poverty (the increased economic vulnerability resulting from the financial burden posed by the need for menstrual supplies) and promote period equity.

To learn more about Period Poverty and Equity, on Campus and Beyond, visit https://chrr.info/current-projects-2/past-projects/period-poverty-and-equity-on-campus-and-beyond/.

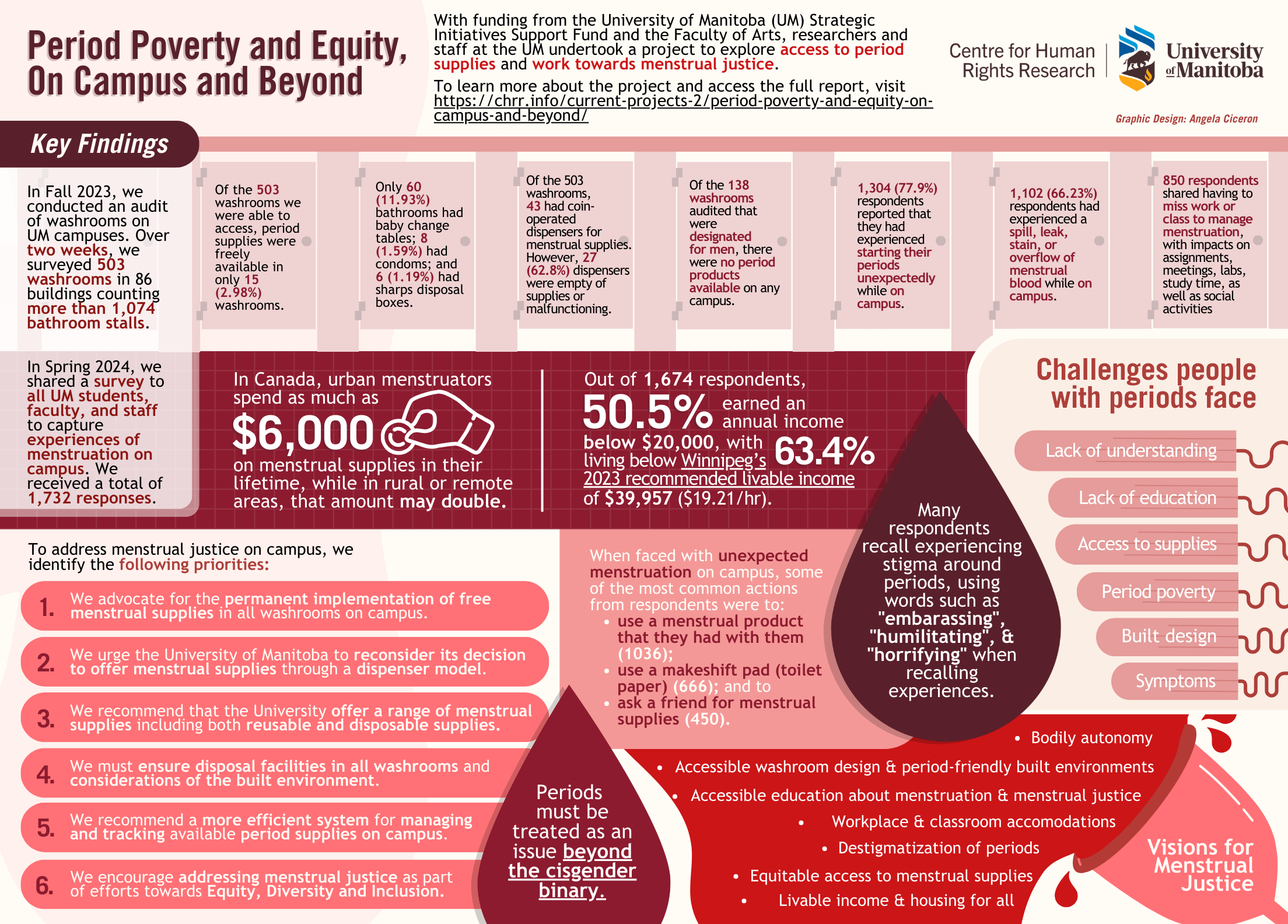

Period Poverty and Equity, On Campus and Beyond Infographic

Period Poverty and Equity, On Campus and Beyond Infographic

August 2, 2024

Graphic Design: Angela Ciceron

In 2023, with funding from the Centre for Human Rights Research (CHRR), the Faculty of Arts, and the University of Manitoba’s Strategic Initiatives Support Fund, a group of researchers affiliated with the CHRR came together to explore and address menstrual equity on campus. The “Period Poverty and Equity, On Campus and Beyond” project undertook a campus audit of washrooms to assess availability of menstrual supplies; a survey open to UM students, staff, and faculty; as well as a number of outreach events.

Working towards period equity is not as a charitable endeavour to be ameliorated by donations of period supplies; rather menstrual equity is an issue of justice. Shifting the conversation from period poverty to menstrual justice means asking that all people who menstruate be provided with the resources, tools, and infrastructure to do so with safety and dignity.

Related Resources

Support Us

Whether you are passionate about interdisciplinary human rights research, social justice programming, or student training and mentorship, the University of Manitoba offers opportunities to support the opportunities most important to you.

Executive Summary: Period Poverty and Equity, On Campus and Beyond

Executive Summary: Period Poverty and Equity, On Campus and Beyond

2024

Pauline Tennent et al.

In 2023, with funding from the Centre for Human Rights Research (CHRR), the Faculty of Arts, and the University of Manitoba’s Strategic Initiatives Support Fund, a group of researchers affiliated with the CHRR came together to explore and address menstrual equity on campus. The “Period Poverty and Equity, On Campus and Beyond” project undertook a campus audit of washrooms to assess availability of menstrual supplies; a survey open to UM students, staff, and faculty; as well as a number of outreach events.

Working towards period equity is not as a charitable endeavour to be ameliorated by donations of period supplies; rather menstrual equity is an issue of justice. Shifting the conversation from period poverty to menstrual justice means asking that all people who menstruate be provided with the resources, tools, and infrastructure to do so with safety and dignity.

A Report on Period Poverty and Equity, On Campus and Beyond

A Report on Period Poverty and Equity, On Campus and Beyond

June 2024

Pauline Tennent, et al.

In 2023, with funding from the Centre for Human Rights Research (CHRR), the Faculty of Arts, and the University of Manitoba’s Strategic Initiatives Support Fund, a group of researchers affiliated with the CHRR came together to explore and address menstrual equity on campus. The “Period Poverty and Equity, On Campus and Beyond” project undertook a campus audit of washrooms to assess availability of menstrual supplies, a survey open to UM students, staff, and faculty, as well as a number of outreach events.

Working towards period equity is not as a charitable endeavour to be ameliorated by donations of period supplies; rather menstrual equity is an issue of justice. Shifting the conversation from period poverty to menstrual justice means asking that all people who menstruate be provided with the resources, tools, and infrastructure to do so with safety and dignity.

Related Resources

Support Us

Whether you are passionate about interdisciplinary human rights research, social justice programming, or student training and mentorship, the University of Manitoba offers opportunities to support the opportunities most important to you.

Article in The Manitoban: Shortfalls in menstrual equity at U of M, audit reveals

Article in The Manitoban: Shortfalls in menstrual equity at U of M, audit reveals

August 24, 30

Kyra Campbell

Kyra Campbell, reporter for The Manitoban, covered the work of the “Period Poverty & Equity, On Campus and Beyond” project, including the campus audit and the button-making event. Read more at The Manitoban!

Related Resources

Support Us

Whether you are passionate about interdisciplinary human rights research, social justice programming, or student training and mentorship, the University of Manitoba offers opportunities to support the opportunities most important to you.

Contact Us

We’d love to hear from you.

442 Robson Hall

University of Manitoba

Winnipeg, Manitoba

R3T 2N2 Canada

204-474-6453

Quick Links

Subscribe to our mailing list for periodic updates from the Centre for Human Rights Research, including human rights events listings and employment opportunities (Manitoba based and virtual).

Land Acknowledgement

The University of Manitoba campuses are located on original lands of Anishinaabeg, Ininew, Anisininew, Dakota and Dene peoples, and on the National Homeland of the Red River Métis.

Centre for Human Rights Research 2023© · Privacy Policy