Water and Justice Resource Guide

July 23, 2025

Sarah Deckert and Shaylyn Pelikys

The Nibi Declaration of Treaty #3 begins, “Nibi (water) is alive and has a spirit. It is the lifeblood of our mother (aki) and connects everything. It can give, sustain and take life.” Indigenous knowledges teach us to relate to water not as a resource to be extracted but as a living being to be loved and respected. As you engage with the podcasts, documentaries, books and other resources included in this preliminary resource guide, we hope that you will do so while holding on to the central truth of the Nibi Declaration: “Nibi (water) is alive and has a spirit.”

The Lake St. Martin Story

March 12, 2025

Cameron Armstrong

Water control structures have disempowered and displaced First Nations, destroying livelihoods in the name of development, upholding colonial systems and perpetuating environmental racism. One such case is that of Lake St. Martin and the Lake St. Martin First Nation.

As part of the Just Waters project, student RA Cameron Armstrong wrote a plain language summary giving an account of 50+ years of artificial flooding that have impacted the Lake St. Martin First Nation in a myriad of ways, including long term evacuation. Download the resource to find out more.

New project at the CHRR: “Just Waters”

New project at the CHRR: "Just Waters"

July 2, 2024

Pauline Tennent

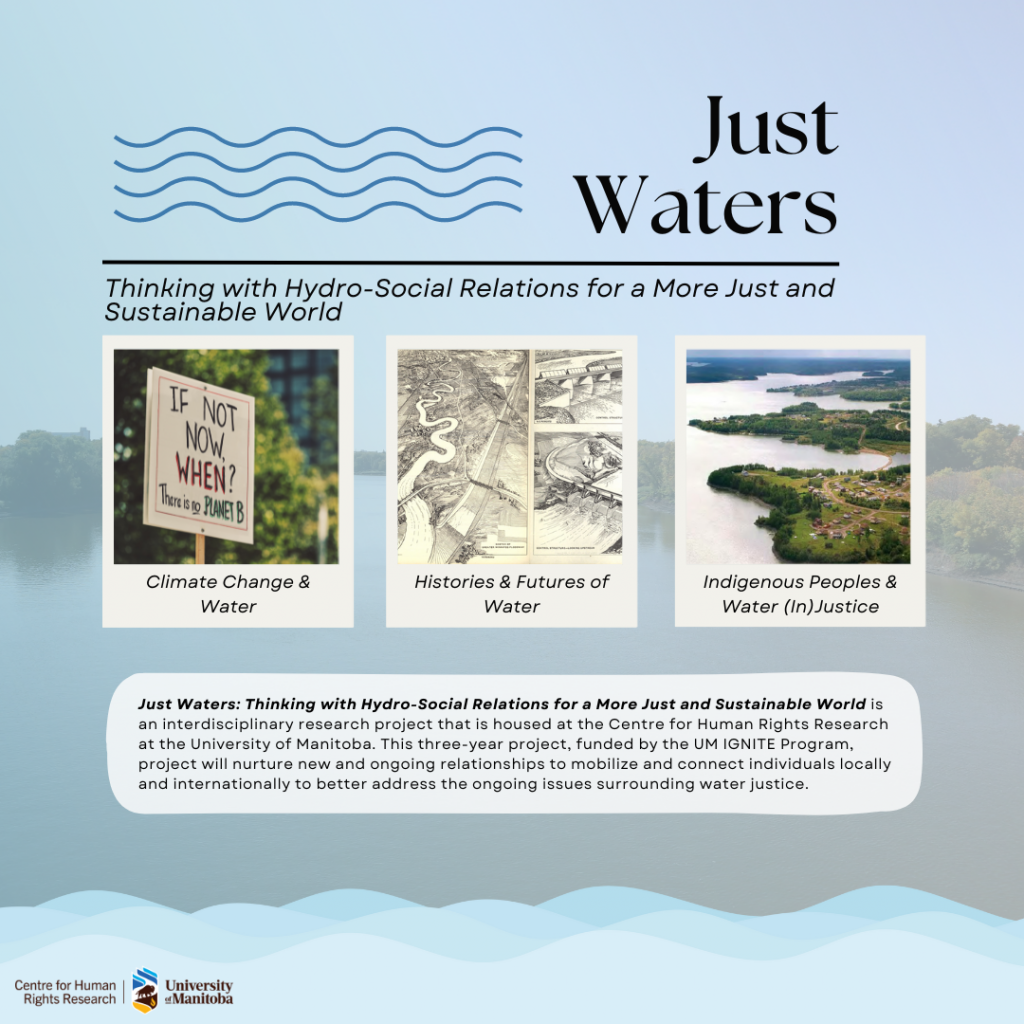

Just Waters: Thinking with Hydro-Social Relations for a More Just and Sustainable World is an interdisciplinary research project that is housed at the Centre for Human Rights Research at the University of Manitoba. This three-year project, funded by the UM IGNITE Program, will nurture new and ongoing relationships to mobilize and connect individuals locally and internationally to better address the ongoing issues surrounding water justice.

Just Waters is led by Dr. Adele Perry, Distinguished Professor in the Faculty of Arts & Director of the CHRR at the University of Manitoba. Just Waters will apply an interdisciplinary lens to water (in)justice and work to move research to the next steps. By establishing an interdisciplinary approach and centering the hydro-social, the project will nurture new and ongoing relationships to mobilize and connect individuals locally and internationally to better address the ongoing issues surrounding water justice.

Just Waters will provide and support relevant, original, and timely responses through three overlapping and interrelated clusters: climate change and water; histories and futures of water; and Indigenous peoples and water (in)justice. These clusters will draw on wide interdisciplinary and interfaculty expertise to shed light on the relationship between water, water injustice, and water justice. For more information, check out the project’s webpage.

Rethinking how we approach research for water justice

Rethinking how we approach research for water justice

May 30, 2024

By: Kiersten Sanderson (she/they)

‘Water and Climate Justice: Advancing Intersectional Approaches’, was held on May 27-28th, 2024 at the University of Manitoba. With funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, it was led by Dr. Nicole J. Wilson, Assistant Professor in Environment and Geography and Research Affiliate with the Centre for Human Rights Research. This workshop was supported by the Centre for Human Rights Research, Centre for Earth Observation Science, Decolonizing Water, the UBC Program on Water Governance, and the Household Water Insecurity Experiences (HWISE) – Research Coordination Network. The workshop culminated in an engaging panel on the evening of the May 28th at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights.

Images: Nick Lupky.

The workshop gathered some of the most incredible and inspiring individuals – scholars, activists, advocates, storytellers – all of whom work in the realm of water and climate justice. An important goal of the two-day workshop was bridging the gap and uniting the diverse disciplines that work on water scholarship. For me, it was this diversity amongst scholars and practitioners represented just how integral the issue was. Many had a background in natural sciences, however there were just as many with humanities and social sciences backgrounds, including history, literature, and governance. A notable observation was that most attendees were women. There was a strong influence and respect towards Indigenous ways of knowledge and philosophies.

I joined the workshop as a Student Research Assistant at the CHRR, working on the newly funded Just Waters project. I was selected as a Research Assistant as part of the Indigenous Summer Student Internship Program. For me, it felt good to return to water justice – to a topic that I’ve always felt passionate about. I’m a part of a generation that has grown up with climate change, water injustices, and inequities all being topics in the curriculum. Throughout high school, I actively participated in our environmental justice student group, which included biannual water testing and sampling at three different sites. Because of my disinterest in the natural sciences, I never considered that I would be able to continue with my interests in academia; the workshop provided me with a chance to meet scholars and professionals who come at the issue from diverse disciplines and perspectives.

Following introductions, together the attendees established themes of knowledge gaps that required further discussion. These four themes included:

- Justice Frameworks

- Procedural Justice

- Unity of Knowledge

- Well-being

This opening exercise was eye-opening. These areas of study don’t exist within silos, the way that we might perceive them to. These issues are as much of social ones as they are scientific. While I might be currently pursuing a career in the legal field there are still ways I can advocate for climate and water justice. There is work to be done, regardless of the educational background one might have. Everyone has a role and a responsibility when it comes to water, and the participation of everyone is integral for our future.

In the months following the workshop, I found myself thinking often of one theme that had been identified by the group – unity of knowledge. The idea was to explore how different areas of study operate in silos, and they remain separate and distinct, with little overlap or little collaboration. This is true for not only the natural sciences and humanities/social sciences, but also western knowledge on water and Indigenous knowledge systems on water. It’s important to integrate all the different forms of knowledge together. This includes how to integrate the natural sciences together with concepts of justice.

I’ve also been thinking back to my participation in water testing in high school at Whitemud River, Manitoba. While testing the water – we considered questions related to the appearance of water and the recreational usage of the water. At one of the sites, a few students shared that they had swam in the water for years; yet there were many of us who hadn’t even considered this water as being suitable for swimming because of the way we perceived the conditions of the water and the surrounding environment. Within the group, we had different relationships with the water. This is an important attribute to the data we collected. While the tests that we would conduct may provide data about whether the water was good for recreational usage, this is in a context where people had ongoing relationships with that water, and different opinions on what makes the water safe for recreational usage. If the results either we or the lab found it to be unsafe, the cause of the problem could be dealt with. The community could also be made aware so they can make decisions for their well-being. Both the tests we conducted, and the information provided by those with ongoing relationships to the site were valuable to the data we collected.

When we think about bridging these silos, it can happen during water testing. When you go out to collect water samples, the testing could also involve questions about your relationship to the water, or questions rooted in Indigenous ways of knowing. This could include asking those taking samples to consider how the condition of the water makes you feel, to document animals that you might’ve seen, or to answer whether you might swim or drink the water. To me, these questions make sense especially when members that are collecting water samples are a mix of those local to the area and those who are not.

Our relationships to water and the various forms of knowledge about water are all important in addressing the complex challenges of water and climate injustices that we face today. The workshop helped me return to my passion. Climate and water justice need to transition to both prioritizing interdisciplinary work and also valuing and respecting Indigenous knowledge (as much as western science typically is) if we are to address the complexities of water injustices.

Thinking with the Ocean: Twelve questions and a meditation to accompany the International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Thinking with the Ocean: Twelve questions and a meditation to accompany the International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade

March 10, 2024

Sonja Boon

“Water,” writes Dionne Brand in A Map to the Door of No Return: Notes to Belonging, “is the first thing in my memory. The sea sounded like a thousand secrets, all whispered at the same time.”[1] What might it mean to read the ocean as whispers and secrets – as an archive? What pasts might float ashore, what new stories might be carried on the currents, what materials might be washed away, eroding into unknowable and irretrievable memories?

As Derek Walcott reminds us, “The sea is History.”[2] The ocean is a repository of human memory, both metaphorical and material. Polluted with the debris of the Atlantic slave trade and histories of indenture, as well as the muck of penal ships, refugee journeys, and other detainments, these seas are not the “timeless, unchanging, unmarked, deeply unhistoric” waters of our imagination.[3] Rather, the ocean – whose histories are shaped by imperial quests for wealth, domination and control – is unknowable. Too vast, it is overwhelming. Too mobile, it challenges desires for fixity, solidity, and control.[4] Time, here, is not linear; rather, it is relational, experienced through the interaction of different forces – terrestrial, aqueous, and lunar.

If the ocean is unbounded, how might this unboundedness also allow us to imagine the archives of enslavement differently: What happens when archives of containment, capture, violence, and indeed erasure, flood?[5] When stories exceed their banks? When identities rupture, surge, spill, overflow, escape?[6] Alternatively, following Carolyn Steedman, if archives are places of dreams,[7] then what might it mean to imagine lost, silenced, and forgotten dreams through oceanic swells, currents, sprays, and saltings?

Scholars and poets of the Black Atlantic figure water – here understood primarily as the Atlantic of the Middle Passage – as a site of haunting that is both life giving and life destroying. In the words of Guyanese poet Grace Nichols, “Yes, I rippling to the music / I slipping pass the ghost ships / Watching old mast turn flowering tree / Even in the heart of all this bacchanal / The Sea returns to haunt this carnival.”[8]Thinking about oceans as archives asks us to honour not only those for whom the ocean has been a grave, but also those who have journeyed across its waves, journeys that transformed people into chattel, erasing names for numbers, journeys haunted by violent erasures and unfinished dreams.[9]

Thinking about oceans as archives asks us also to think about time in relation to memory. In the words of Janine McLeod, the sea might be imagined as “an infinite water in which everything is retained, and where all times mingle together.”[10] Oceanic time cannot be contained in an endless march forward: it cycles forward and back with the tides, washing with the waves, eroding land and memories.[11]

Oceanic archival thinking requires us to interrogate notions of boundaries and borders, the ways that water erodes shorelines, remapping territory and undermining claims to land, and to think about time and geography in relation to memory — “an infinite water in which everything is retained, and where all times mingle together.”[12] Along the shores in Suriname, for example, entire plantations have eroded, their histories – and their violences – claimed by the sea. And yet, in the process, erosion – as a form of oceanic time – has also revealed submerged truths, with lost slave cemeteries rising to the surface.

There is both a softness and a brittleness to oceanic time. Tumbling rocks soften in ocean waves; rough edges become smooth. But we also need to attend to the salting that both hardens and burns, preserves and destroys. We might consider, here, the essential role of salted, preserved fish. Salt fish was fed to the enslaved and remains an essential part of contemporary Caribbean diets, culture, and identity, but also, and simultaneously, is destructive in relation to broader questions of health. But we can also look to the material conditions of enslaved labour. In The History Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave, Mary Prince recounts her time working in the salt ponds on Grand Turk, Turks and Caicos Islands, and the sores, boils, and blisters that ate right down to the bone.[13]

In the haunted space-time of oceans as archives, past, present, and impossible-but-hoped-for futures collide with one another. How can we make sense of histories of ruination? How can we, following M. NourbeSe Philip, tell impossible stories that must be told?[14] But also, how can we live well in what Christina Sharpe calls the wake, a mode of reckoning and a reminder of a “past that is not yet past,”[15] in the ongoing afterlives of the transatlantic slave trade? What stories might the ocean be able to tell us, and what might we learn? What might it mean, following Alexis Pauline Gumbs, to breathe with the ocean?[16]

The work of artist and scholar Camille Turner offers one way forward. In 2019, when interviewed about an art installation that considered Newfoundland and Labrador’s imbrication in the transatlantic slave trade, she underscored the importance of understanding these pasts. “We didn’t create this history,” she said. “None of us did. We weren’t here, but it is what shaped us. By not dealing with it, we can never move on from here. We can’t really move into a future where things are equitable. So I think it’s really important to acknowledge these stories.”

This blog post draws on an essay I wrote for Daze Jefferies: Stay Here Stay How Stay (St. John’s: The Rooms Provincial Art Gallery, 2024), as well as on “Thinking with Oceans,” a blog post I wrote for the Social Sciences and Humanities Ocean Research and Education (SSHORE) network (https://sshoresite.wordpress.com/2019/05/27/thinking-with-oceans/). My thanks to The Rooms Provincial Art Gallery for permission to quote from the essay.

[1] Dionne Brand, A Map to the Door of No Return: Notes to Belonging, Toronto: Penguin Random House, 2001, 8.

[2] Derek Walcott, “The Sea is History,” in Collected Poems, 1948-1984. New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 364. https://www.theparisreview.org/poetry/7020/the-sea-is-history-derek-walcott

[3] Suvendrini Perera, “Oceanic Corpo-Graphies, Refugee Bodies and the Making and Unmaking of Waters.” Feminist Review 103 (2013): 58-79, 62.

[4] See, for example, Renisa Mawani’s oceanic methodology in Across Oceans of Law (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), which relies on currents layering over and against one another.

[5] For more on flooding and memory, see Toni Morrison, “The Site of Memory,” where she writes: “You know, they straightened out the Mississippi River in places, to make room for houses and livable acreage. Occasionally the river floods these places. ‘Floods’ is the word they use, but in fact it is not flooding; it is remembering. Remembering where it used to be. All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was” (“The site of memory.” In Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir, ed. William Zinsser, 83-102. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1995, 98-99.

[6] See, for example, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Spill: Scenes of Black Feminist Fugitivity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016).

[7] Carolyn Steedman, Dust: The Archive and Cultural History (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2002).

[8] Grace Nichols, I Have Crossed an Ocean, Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Bloodaxe Books, 2010, 103.

[9] For one powerful example of restorying the Middle Passage, see M. NourbeSe Philip, Zong!, Westeyan University Press, 2008.

[10] Janine McLeod. “Water and the Material Imagination: Reading the Sea of Memory against the Flows of Capital.” In Thinking With Water, eds. Cecilia Chen, Janine McLeod, and Astrida Neimanis, 40-60 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2013), 40.

[11] Stefanie Hessler, “Tidalectics: Imagining an Oceanic Worldview through Art and Science.” In Tidalectics: Imagining an Oceanic Worldview Through Art and Science, ed. Stefanie Hessler, 31-81 (Boston: MIT Press, 2018); Mawani, Across Oceans of Law; and McLeod. “Water and the Material Imagination.”

[12] McLeod, “Water and the Material Imagination,” 40.

[13] Mary Prince, The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave. London: F. Westley and A.H. Davis, 1831)

[14] M. NourbeSe Philip, Zong!, Wesleyan University Press, 2008.

[15] In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 13.

[16] Gumbs, Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals (Chico, CA: AK Press, 2020).

Contact Us

We’d love to hear from you.

442 Robson Hall

University of Manitoba

Winnipeg, Manitoba

R3T 2N2 Canada

204-474-6453

Quick Links

Subscribe to our mailing list for periodic updates from the Centre for Human Rights Research, including human rights events listings and employment opportunities (Manitoba based and virtual).

Land Acknowledgement

The University of Manitoba campuses are located on original lands of Anishinaabeg, Ininew, Anisininew, Dakota and Dene peoples, and on the National Homeland of the Red River Métis.

Centre for Human Rights Research 2023© · Privacy Policy