Abortion in Manitoba: A Feminist Community-Based Approach to Abortion Access Research

January 28, 2026

Hannah Belec

In collaboration with the University of Manitoba Faculty of Arts, the Centre for Human Rights Research hosted Dr. Lindsay Larios and Emma Cowman for a lecture titled ‘Abortion in Manitoba: A feminist community-based approach to abortion access research’. The lecture was held on Wednesday, January 28, 2026 at the University of Manitoba – Fort Garry Campus.

This seminar is a part of our annual Critical Conversations seminar series. This year, the seminar series focuses on feminist research methodologies, exploring various ways research is done within feminist and anti-oppressive scholarship.

Watch the lecture below.

Abortion in Manitoba: An Overview of Care – Community Report

Abortion in Manitoba: An Overview of Care - Community Report

January 21, 2026

Emma Cowman, Lindsay Larios, O. Thomas, and Melanie Paterson

Although abortion is legally treated as a standard medical procedure in Canada, the landscape of abortion access in Manitoba remains shaped by social, political, and geographic realities. People across the province continue to encounter barriers such as long travel distances, limited appointment availability, lack of local providers, abortion an stigma, among other challenges. Collectively, these challenges shape access to abortion care in Manitoba as fragmented, inconsistent, and highly dependent on context.

The Abortion in Manitoba project was developed to document the realities of those who have sought access to abortion care in the province. Drawing on survey responses and narrative interviews, the community report highlights key barriers, sources of support, and gaps in care across all stages of the abortion experience. The findings and recommendations aim to inform policy, healthcare practice, and community advocacy, and to support more equitable, accessible, and just abortion care in Manitoba.

Just Research: A Podcast – Episode 1

Just Research: A Podcast - Episode 1

October 6, 2025

Angela Ciceron

If you’re interested in water justice, you’ll be interested in the first episode of Just Research. Just Research is a podcast series from the Centre for Human Rights Research at the University of Manitoba. Hosted by Dr. Pauline Tennent and Dr. Adele Perry, the podcast highlights researchers from the UM community and beyond doing work in human rights and social justice in a variety of disciplines.

This season focuses on researchers whose work engages with each of the CHRR’s research themes: Borders and Human Rights, Indigenous Peoples and Human Rights, Reproductive and Bodily Justice, and Water Rights and Justice.

Episode 1: Looking Back on the CHRR and Water Research with Helen Fallding

In the first episode of Just Research, CHRR director Dr. Adele Perry and former CHRR manager Helen Fallding look back to the CHRR’s longstanding work in water rights and justice. In this conversation, they talked about the CREATE H2O program, its interdisciplinary, foundational work in water and sanitation in First Nations communities, and its legacy through the Just Waters project.

Listen now:

Beyond the Binary: Celebrating Trans, Non-Binary, & Gender-Expansive Folks on International Women’s Day

Beyond the Binary: Celebrating Trans, Non-Binary, & Gender-Expansive Folks on International Women’s Day

March 7, 2025

Emma Cowman (she/they)

Image: Juan Moyano / Stocksy United

International Women’s Day (IWD) is a day to celebrate the social, economic, cultural, and political achievements of women. This is a day to celebrate the resilience and accomplishments of those oppressed under patriarchal systems, while serving as a reminder of the ongoing global struggles for gender equity and justice. However, this day of celebration has historically centered on the experiences of cisgender women, often excluding or disenfranchising trans, non-binary, and gender-expansive folks, who also experience misogyny, gender-based violence, and discrimination under patriarchal systems.

With our neighbours in the U.S. outwardly attacking trans rights through policy and legislative changes, it is imperative to recognize and uplift trans folk this IWD. These legislative assaults – including restrictions on gender-affirming care, bathroom access, legal gender recognition, and the removal of gender identity from state civil rights protections – threaten the dignity and safety of trans individuals.

However, these attacks are not just a U.S. issue. Across the world, trans communities are fighting for their basic human rights in the face of state-sanctioned violence, exclusion, and systemic barriers to healthcare, education, and legal recognition. In Canada, while trans and non-binary people are recognized and protected under Canadian law, the current Conservative Party opposition leader, Pierre Poilievre has stated that he is only aware of two genders (male and female). Furthermore, provincial governments across the country are attacking trans, non-binary, and gender-expansive youth through pronoun and name laws in Saskatchewan, Alberta, and New Brunswick schools.

Trans Rights are Human Rights

At its core, the fight for gender equality is a human rights issue. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights affirms that all individuals, regardless of gender identity, are entitled to dignity, freedom, and equality. Further, international human rights law protects 2SLGBTQIA+ people from discrimination and violence. Trans people have the right to legal recognition of their gender identity, the right to change their gender in official documents, and the right to access education, employment, and healthcare.

Despite this, trans, non-binary, and gender-expansive folks experience discrimination and trans misogyny in healthcare, employment, education, and housing. They are also at a higher risk of experiencing hate-motivated violence, including physical and sexual assault.

The failure to fully recognize trans rights as human rights reinforces cycles of marginalization, violence, and state-sanctioned discrimination. When governments pass laws that restrict gender-affirming care, erase legal gender recognition, or criminalize trans existence, they are not just enacting policy – but they are violating the basic human dignity and rights of trans individuals. These actions send a dangerous message that trans lives are disposable, further legitimizing social stigma and violence against trans communities.

By affirming that trans rights are human rights, we acknowledge that true gender equality cannot be achieved without the full inclusion, protection, and empowerment of trans, non-binary, and gender-expansive individuals. Human rights belong to everyone – not just those who conform to rigid, binary understandings of gender. Ensuring that trans people have access to the same freedoms, opportunities, and protections as everyone else is not just an act of solidarity, but a necessary step toward building a more just and equitable world.

This International Women’s Day…

This IWD, we must honour trans, non-binary, and gender-expansive folks who have long been at the forefront of feminist, 2SLGBTQIA+, and social justice movements, even when they are being erased from these narratives. From Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera in the fight for queer and trans liberation, to contemporary leaders like Raquel Willis, Imara Jones, and Tourmaline, trans activists have been pivotal in challenging systemic oppression, advocating for bodily autonomy, and demanding gender justice for all. As we mark IWD, we must ensure that trans, non-binary, and gender-expansive individuals are not just included in the conversation but actively centered in the fight for gender justice and freedom from patriarchal oppression.

International Women’s Day is a call to action to dismantle the oppressive structures that harm all women – cis and trans alike – alongside trans men, non-binary, and gender-expansive individuals. This IWD must be a day that centers and celebrates the resilience, contributions, and struggles of trans, non-binary, and gender-expansive people worldwide. At the same time, we emphasize the need for continued advocacy to challenge the rising gender essentialist rhetoric and legislation. By recognizing the intersections of gender oppression, we strengthen the collective fight for liberation, autonomy, and justice for all.

By: Emma Cowman (she/they)

Reflecting on a Decade of Pro-Choice Student Activism at the University of Manitoba’s Fort Garry Campus

Reflecting on a Decade of Pro-Choice Student Activism at the University of Manitoba’s Fort Garry Campus

March 7, 2025

Hannah Belec (she/her)

Warning: This photo essay describes the use of abortion imagery and anti-choice rhetoric. All abortion imagery in the featured photos has been covered

“My or your freedom should not infringe on someone else’s freedom.”

– Kemlin Nembhard, Executive Director of the Women’s Health Clinic at “My Body, My Choice, Our Struggle: A Conversation on Reproductive Justice.”

“If you cannot control your own body, you cannot control your life.”

– Linda Taylor, Founding Board Member of the Women’s Health Clinic at “My Body, My Choice, Our Struggle: A Conversation on Reproductive Justice.”

Introduction

In honour of International Women’s Day, this photo essay highlights and commends University of Manitoba (UM) students who have, for more than a decade, counterprotested and launched initiatives against anti-choice groups on UM’s Fort Garry Campus (FGC). These students have challenged harmful anti-choice narratives and imagery, advocated for a safer campus, and pushed for improved access to reproductive education and healthcare. They have strived to ensure that fellow UM students can make informed choices about their bodies.

However, this photo essay reveals that, unlike UM students, UM administration has remained passive in addressing anti-choice groups on UM’s FGC. UM administration must act against anti-choice groups and establish policies, such as enforcing an abortion protest buffer zone, to create a safe and supportive campus environment for all UM students.

Photo by Fraser Nelund and article by Quinn Richert. Abortion debate front and centre at the U of M: Student group compares abortion with graphic genocide imagery. The Manitoban. October 2, 2013. Available at: https://issuu.com/themanitoban/docs/manitoban2oct2013.

At the start of the 2013-2014 academic year, the anti-choice student group UM Students for a Culture of Life (UMSCL), with permission from UM administration, set up a graphic display that equated the Holocaust and Rwandan Genocide with abortion. In response, a group of UM students staged a counterprotest to challenge the display’s dangerous and misleading messaging.

Andrew Woolford, a UM Professor of Sociology, and Genocide Scholar, spoke in solidarity with the student counter-protesters. Speaking to The Manitoban, he criticized the display stating, “it does little to foster intelligent debate when everyone who supports [the] right to choose is placed in the position of being a genocide denier or genocidaire.”

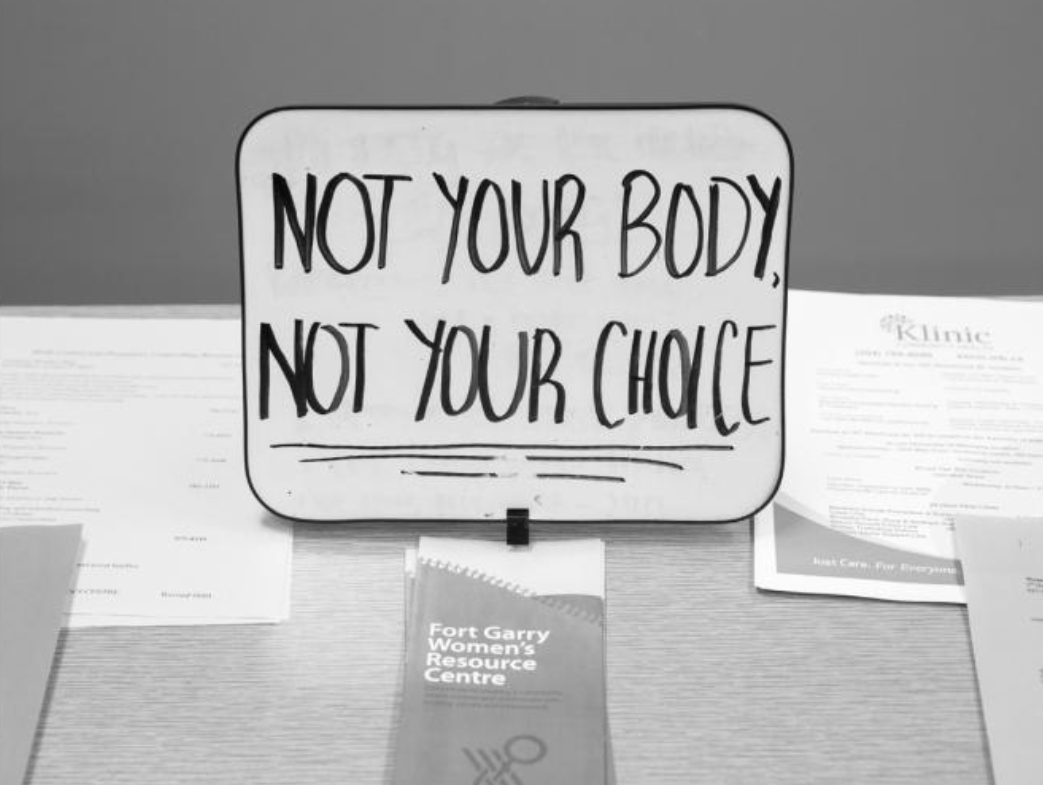

Photo by Chantal Zdan and article by Diana Ubokudom. Pro-life student group workshop met with protest: Students express disapproval of University of Manitoba Students for a Culture of Life. The Manitoban. October 18, 2017. Available at: https://issuu.com/themanitoban/docs/09_2017_oct_18_web.

On October 12th, 2017, UMSCL hosted a “Pro-Life 101” workshop on the UM’s FGC to advance their pro-life agenda with attendees. However, the event was disrupted by pro-choice UM students, seen in the image above. The students distributed reproductive health pamphlets and shouted pro-choice sayings to workshop attendees.

One of the pro-choice students, Maya Martinez, shared with The Manitoban that the “[pro-choice students] think that [UMSCL] intimidate [students] on campus who have had abortions or are looking to have abortions.”

Photo by Quincy Houdayer and article by Shaden Abusaleh. Anti-abortion group asked to leave Fort Garry campus: UMSAN-RSM holds workshop on combating “anti-choice” groups. The Manitoban. February 7, 2018. Available at: https://issuu.com/themanitoban/docs/22_2018_feb_7_web.

Due to the presence of UMSCL and the Canadian Coalition for Bio-Ethical Reform (CCBR) on UM’s FGC, the UM Student Action Network – Revolutionary Student Movement (UMSAN-RSM) hosted a workshop on February 1st, 2017, called “Proletarian Feminism: Combatting Anti-Choice Groups in Winnipeg.”

Elizabeth McMechan, a UMSAN-RSM member and one of the event’s organizers, said that “a lot of [anti-choice rhetoric] is inherently misogynistic and wrong and [she doesn’t] think that University of Manitoba students should be subject to that when they’re trying to be in safe space to get their education.” McMechan further explained that UMSAN-RSM was committed to limiting the presence of anti-choice groups on UM’s FGC.

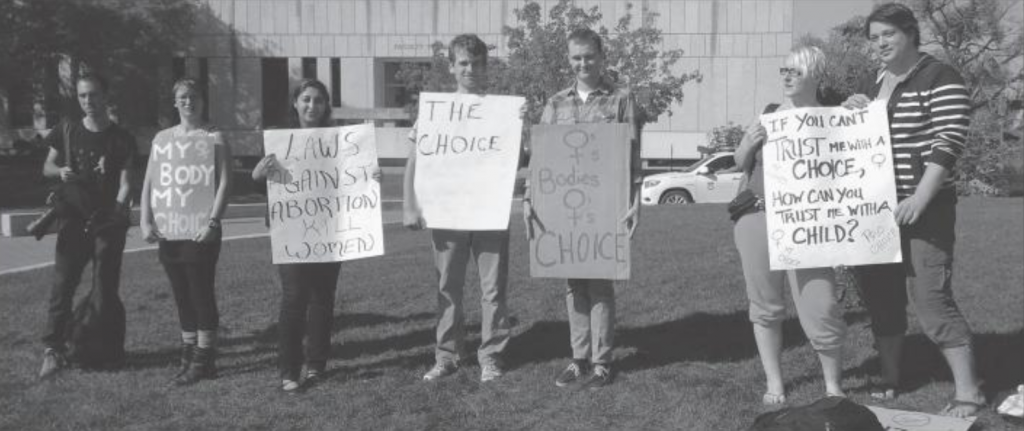

Photo by Sahar Azizkhani and article by Malak Abas. Pro-life campaign sparks protest outside UC: Dispute over reproductive rights debate and its place in public spaces. The Manitoban. October 24, 2018. Available at: https://issuu.com/themanitoban/docs/12_2018_october_24_online_.

On October 22nd, 2018, UM students organized a counterprotest in front of the University of Manitoba Students’ Union (UMSU) University Centre where members of the CCBR displayed images of aborted fetuses and attempted to engage passersby in pro-life discussions.

Shannon Furness, who was involved in the counterprotest and the UM Arts Student Body Council (ASBC) Women’s Representative at the time, explained to The Manitoban that “the demographic that most get abortions is 18 to 24, so [the CCBR] are here for a reason… regardless of if [anti-choice groups] are actually directly restricting our reproductive rights – which they’re not at this point – it still can impact [one’s] right to choose… it can make them feel victimized, vulnerable, or ashamed.”

Another student who participated in the counterprotest, Elizabeth McMechan from UMSAN-RSM, stated that she believes “it’s important that the university make a statement about whether or not they’re going to support a student’s right to bodily autonomy.”

Photo by Alexander Decebal-Cuza and article by Malak Abas. UMSU, ASBC advance motions on pro-life groups: Councils will vote to oppose “coercion” by reproductive rights groups; UMSU motions support reproductive rights: Board passes amendments to position statement, safe environment policy. The Manitoban. October 31 and November 7, 2018. Available at: https://issuu.com/themanitoban/docs/13_2018_october_31_online_ and https://issuu.com/themanitoban/docs/14_2018_november_7_online_.

In response to concerns raised by UM students about the presence of the CCBR and UMSCL on UM’s FGC, UMSU’s Board of Directors approved significant amendments to UMSU’s Safe Environment Policy and Equitable Campus Position Statement on November 5th, 2018.

Motion 0428A updated the Equitable Campus Position Statement to affirm UMSU’s support for “one’s right to freedom of reproductive choice; and one’s right to be free from coercion or attempted coercion with respect to making reproductive choices.”An additional sub-clause clarified that UMSU does not support “any act of coercion or attempted coercion with respect to making reproductive choices” or “the dissemination of graphic material or information that is misleading or false as part of any event/activity or within the group/club or association.”

Motion 0428B revised the Safe Environment Policy to explicitly include “any act of coercion or attempted coercion with respect to making reproductive choices”under the definition of “discriminatory or harassing behaviours and actions.”

Concurrently, ASBC introduced a motion that aimed to prevent the display of “graphic images and the targeting of vulnerable individuals” by the CCBR, UMSCL, and other anti-choice groups in Faculty of Arts buildings.

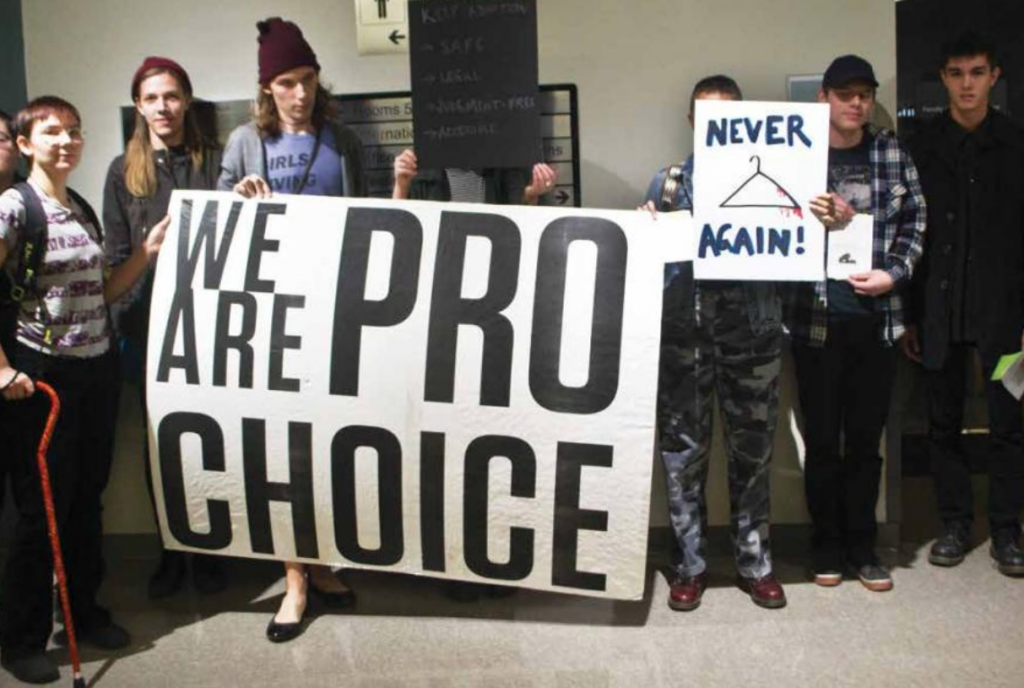

Photo by Ebunoluwa Akinbo and article by Colton McKillop. Anti-abortion group CCBR holds rally on campus: Graphic images of aborted fetuses met with counter-protest. The Manitoban. September 14, 2022. Available at: https://issuu.com/themanitoban/docs/109_05_sep14_2022.

In less than 24 hours, the UMSU Women’s Centre (WC) and Justice for Women Manitoba (JWM) organized a student counterprotest in response to the CCBR’s anti-choice presence on UM’s FGC in September 2022.

Jessica Gibson, President of JWM at the time, condemned the CCBR’s use of images of aborted fetuses, calling them “triggering and retraumatizing.”

UMSU also issued a statement on Instagram, emphasizing its commitment to student well-being: As “a union meant to support our student body and protect them from harm… [UMSU] cannot sit idly by when some attempt to shame our students for making personal choices about their own lives and futures.”

Gibson urged UM administration to take more decisive action to protect students from distressing material and anti-choice demonstrations on campus, arguing that the university’s existing warning posters were insufficient.

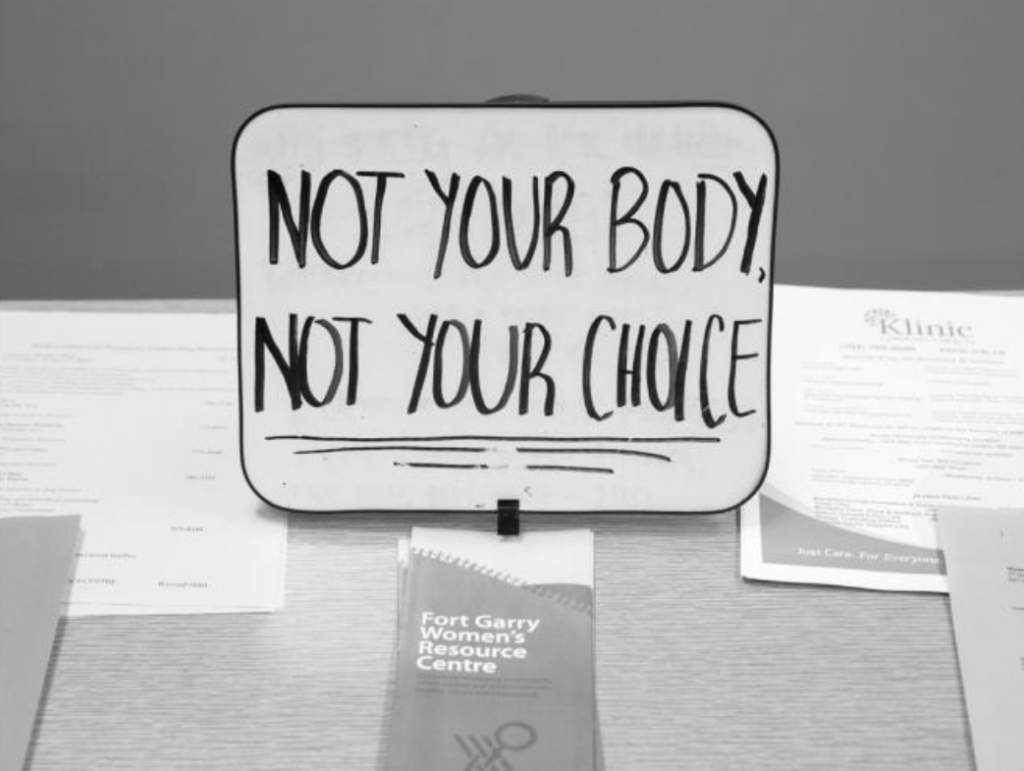

Photo by Ebunoluwa Akinbo and article by Alicia Rose. Student groups hold pro-choice initiative: Event comes as a response to anti-abortion group presence on campus. The Manitoban. April 5, 2023. Available at: https://issuu.com/themanitoban/docs/109_28_apr05_2023.

Taking an approach beyond traditional pro-choice counterprotests, the UMSU WC, JWM, and ASBC launched an initiative to support students during anti-choice demonstrations on the UM’s FGC in late March and early April 2023.

This initiative included distributing reproductive health resources and extending the UMSU WC’s hours to provide a safe space where students could seek support and information. Designed to minimize the negative mental health impacts of direct engagement with anti-choice demonstrators, who often use graphic imagery and start inflammatory debates, this initiative prioritized student well-being while promoting informed choice.

Photo courtesy of the UMSU Women’s Centre.

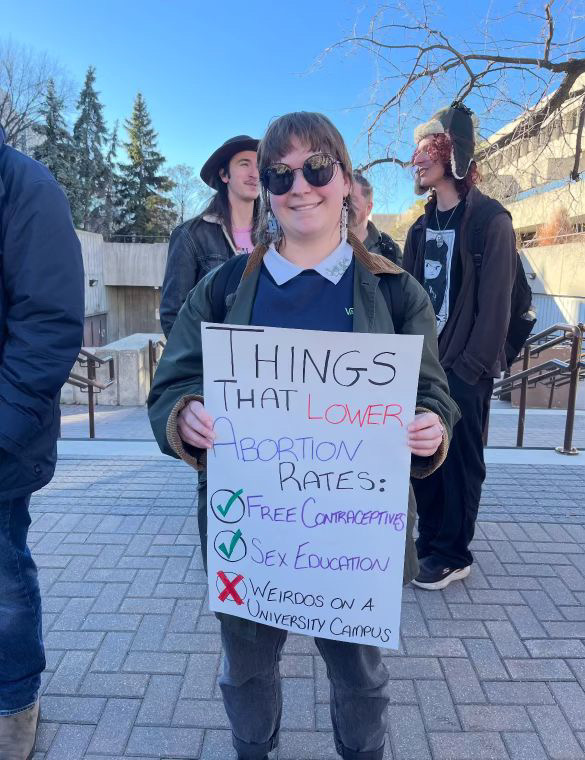

On November 9th, 2024, the UMSU WC held a counterprotest against an anti-choice group outside UMSU University Centre. This anti-choice demonstration and counterprotest came just days after the re-election of U.S. President Donald Trump, whose hand-selected Supreme Court Justices overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022. Since his re-election, Trump’s administration has only continued to threaten reproductive rights in the U.S., impacting many American UM students.

In conversation with Brie Willoughby, the UM student pictured above, they said they are “a firm believer that everyone has a fundamental right to control their own body and make decisions about what happens to it.”

Willoughby expressed frustration with anti-choice groups who come to UM’s FGC with “triggering and falsified images to essentially demonstrate that people don’t deserve to decide whether or not to be pregnant.”

Upon hearing that the UMSU WC was holding a counter-protest, Willoughby “immediately knew [they] had to be part of it.”

Overall, Willoughby was “incredibly heartened by how many people showed up to demonstrate, that [UM] students do not agree with [anti-choice demonstrators], and that [UM students] fiercely defend the right to decide what happens to one’s body.”

Conclusion

For over a decade, pro-choice student activists on UM’s FGC have driven change and worked to protect the well-being and reproductive autonomy of the UM student community. However, the responsibility of safeguarding the UM student community should not rest solely on students. It is time for UM administration to take action against anti-choice groups on UM’s FGC, ensuring that all students feel safe, supported, and empowered in their education and reproductive choices.

By: Hannah Belec (she/her)

Environmental Impact of Period Management Options

Environmental Impact of Period Management Options

May 31, 2024

Chloe Vickar (she/her)

Image: Ebunoluwa Akinbo

Although period management options have improved significantly in the last half century, there is still work to be done to improve period products for the well-being of those who use them, and the well-being of the environment. As we work towards implementing menstrual justice in our communities, we must also prioritize the environmental cost of menstruating.

The environmental impact of period products can be measured by looking at the use of raw materials, energy, and water during the manufacturing processes, the makeup of the components of the products (plastic versus cotton, for example), the packaging of the products, and the total quantity of how many products are used and disposed of globally. However, there is little available literature on the exact environmental impact of disposable period products.

In addition to pads, tampons create significant waste. In the United States, approximately 12 billion pads and 7 million tampons are used each year. The plastic applicators are often marketed as recyclable; however, these pieces are rarely actually recycled. The presence of blood/organic matter disqualifies the applicators from being eligible to recycle in most jurisdictions. Further, as much as 400 pounds of packaging from period products is discarded for each person that menstruators in their lifetime.

Many reusable period products are available as alternatives to disposable pads and tampons. Menstrual cups, discs, reusable pads, and period underwear are among the most popular. Cups and discs are worn internally and made of medical grade silicone, or other body-safe ingredients like TPE, and can be washed and reused for up to 10 years, depending on the brand and the user. In addition to their environmental benefits, cups and discs often hold more menstrual blood than pads and tampons. There are many options for shape, size, and capacity, depending on the menstruator’s anatomy and flow.

Period underwear is increasing in popularity in recent years. It features an absorbent gusset and can be washed and reused for years. Period underwear often holds less menstrual blood than cups or discs but can be worn as backup for leaks in addition to an internal product, or by itself during spotting or for those with a light flow.

There are options for disposable pads and tampons that have lighter environmental footprints than plastic-based products. Pads and tampons made of cotton are healthier for the person using them and for the environment.

Reusable products are not suitable for all bodies, lifestyles, and circumstances, for example due to lack of resources, education, or personal preference. While reusable period products can last many years, they have higher upfront costs than disposable products. Further, internal reusable options such as cups and discs may not work well for all bodies, as each menstruator has different preferences based on their individual needs. Reusable pads are a great option for reducing waste, however one must be able carry the used pad with them until they can be laundered. Therefore, healthier disposable options made from organic cotton are important.

This savings calculator from Winnipeg-based reusable period product company Tree Hugger Cloth Pads illustrates financial and environmental savings from switching to reusable cloth pads.

Environmental impact must be taken into consideration when conceptualizing period products, however disposable options continue to be necessary. The waste associated with disposable products cannot be used as an argument to discourage the importance of free period products. We can advocate for accessibility of products, including disposable and reusable products, so that all menstruators have safe and reliable products.

For more information about the environmental impact of period products, check out these resources:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/wellness/2023/09/12/period-products-absorption-study-blood

Hand, J., Hwang, C., Vogel, W., Lopez, C., & Hwang, S. (2023). An exploration of market organic sanitary products for improving menstrual health and environmental impact. Journal of Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene for Development, 13(2), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2023.020

Harrison, M. E., & Tyson, N. (2023). Menstruation: Environmental impact and need for global health equity. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 160(2), 378–382. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.14311

https://www.treehuggerclothpads.com

https://www.treehuggerclothpads.com/pages/savings-calculator

May 28th is menstrual hygiene day, and this year, the theme is “Together for a #PeriodFriendlyWorld.” While this observance was originally framed as menstrual hygiene – we follow the lead of the World Health Organization, who calls for menstrual health to be recognized, framed, and addressed as a human rights issue, not a hygiene issue. Framing menstruation as such is a reflection of the taboo and stigma around periods. The labelling of period supplies as “feminine hygiene products” is incorrect since as Dr. Jen Gunther explains “needing them is not a sign of being feminine – it’s a sign that you need something to catch blood – and they’re not hygiene products because menstruating is not unhygienic.”

In 2023-2024, the Centre for Human Rights Research at the University of Manitoba has worked on the “Period Poverty & Equity, On Campus and Beyond” project to assess access to period supplies for the University of Manitoba community and to work towards menstrual equity, on campus and in the community. This series of essays is part of the Period Poverty & Equity, On Campus and Beyond project and aims to explore issues of menstrual justice that are often overlooked.

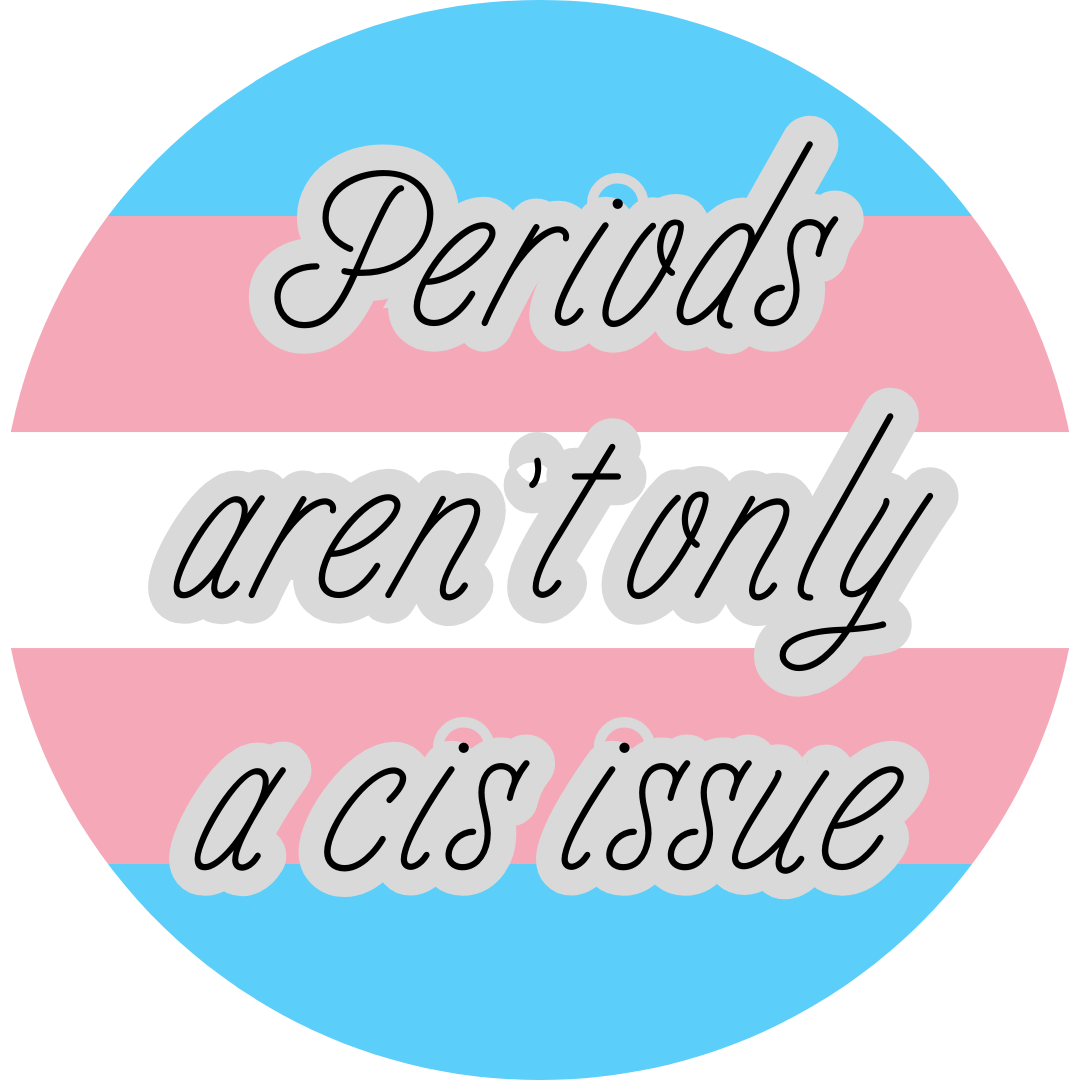

Menstruation and Gender: Beyond Cisgender

Menstruation and Gender: Beyond Cisgender

May 28, 2024

Mikayla Hunter (she/they)

Image by Mikayla Hunter

It is not only cisgender women who menstruate. For some, this idea may be something they are already aware of and understand to be true. For others, it may be a little more difficult. To understand that menstruation is not an experience specific to women, we must first understand what we mean by gender.

The term cisgender refers to a person whose gender identity aligns with the sex they were assigned at birth.1 Transgender is a term for people whose gender identity does not align with the sex they were assigned at birth.1 It is important to note that both ‘cis’ and ‘trans’ are simply prefixes that add additional information to a word or an idea, and neither of these terms are slurs. For example, we can refer to a book as a hardcover book to give more information about the book that we are talking about. Cis is a prefix that means ‘on the same side as’ and trans means ‘on the other side of’. This means that a cisgender woman is a woman whose gender identity is ‘on the same side as’ the sex she was assigned at birth. A transgender man is a man whose gender identity is ‘on the other side of’ the sex he was assigned at birth. With these ideas in mind, we can understand that both cisgender women and transgender men may have a uterus and experience menstruation. However, it is not just cisgender women and transgender men who may have these experiences.

Gender diverse people have a wide range of gender identities and/or gender expressions that do not conform to socially defined gender norms of men and women.2 There are many terms and identities that people may use to describe themselves including non-binary, agender, genderqueer, and gender non-conforming to name a few. Gender diversity does not look a specific way, and the experiences of gender diverse people can (and do) vary. For example, not every gender diverse person will dress androgynously and not all of them will experience menstruation. However, some of them will. Similar to how both cisgender women and transgender men can experience menstruation, so can gender diverse people. A person who menstruates doesn’t look any one specific way or identify as a woman.

Importantly, menstruation can cause gender dysphoria for transgender and gender diverse people. Gender dysphoria is the experience of discomfort or distress because there is a mismatch between a person’s sex assigned at birth and their gender identity.3 For some transgender and gender diverse people, they may undergo procedures such as hysterectomy to relieve gender dysphoria and as a part of their gender journey. However, not everyone has access to these surgical procedures for a variety of reasons and so, menstruation can be all the more difficult for transgender and gender diverse people.

Femininity and menstruation do not go hand-in-hand. A person’s gender identity is their internal sense of gender, or lack thereof. The biological function of our bodies is not directly tied to our gender identities. And so, saying that only women menstruate is incorrect. As Kimberlé Crenshaw explains,4 when policies that support women only support women and policies that support Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour (BIPOC) people only support BIPOC men, BIPOC women are not supported by either policy. When we consider the idea of menstrual equity, we need to ensure that all bodies that menstruate are included and not just cisgender women. Otherwise, we haven’t achieved menstrual equity at all if people are being left out of advocacy and policy changes.

References

[1] Rainbow Center. (2018). Rainbow Center’s LGBTQIA+ dictionary. The University of Connecticut.

[2] https://www.dictionary.com/browse/gender-diverse

[3] https://www.stonewall.org.uk/list-lgbtq-terms

[4] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ViDtnfQ9FHc

May 28th is menstrual hygiene day, and this year, the theme is “Together for a #PeriodFriendlyWorld.” While this observance was originally framed as menstrual hygiene – we follow the lead of the World Health Organization, who calls for menstrual health to be recognized, framed, and addressed as a human rights issue, not a hygiene issue. Framing menstruation as such is a reflection of the taboo and stigma around periods. The labelling of period supplies as “feminine hygiene products” is incorrect since as Dr. Jen Gunther explains “needing them is not a sign of being feminine – it’s a sign that you need something to catch blood – and they’re not hygiene products because menstruating is not unhygienic.”

In 2023-2024, the Centre for Human Rights Research at the University of Manitoba has worked on the “Period Poverty & Equity, On Campus and Beyond” project to assess access to period supplies for the University of Manitoba community and to work towards menstrual equity, on campus and in the community. This series of essays is part of the Period Poverty & Equity, On Campus and Beyond project and aims to explore issues of menstrual justice that are often overlooked.

Indigenous struggles toward period equity

Indigenous struggles toward period equity

May 29, 2024

Bethel Alemaio (she/her)

Image: Money is Cheaper, Period. By Lauren C.

Many Canadians struggle to gain equitable access to menstrual products. Plan International Canada’s Menstruation in Canada Views and Realities reveals the consequences of unaffordable and inaccessible menstrual products among youth and adults. One in five (22%) of the respondents ration their products, and this number rises to 33% for those with household incomes less than $50,000 (Plan International Canada 2022). A recent report focusing on menstrual needs in northern communities noted that 74% of Indigenous respondents in remote communities and 55% of Indigenous respondents in non-remote communities “sometimes” or “often” have issues accessing menstrual products (Lane 2024). Resulting from this, in recent years, Indigenous leaders nationally have fought for easier access to period products (Toory 2022).

Sol Mamakwa, MPP of northern Ontario, is one such person. In 2021, after Shoppers Drug Mart announced its plan to donate menstrual products to public schools, 120 federally funded First Nations schools were excluded from this distribution. Mamakwa was outspoken about the province’s discriminatory practices, which violated Jordan Principle. Within this policy, it is mandated that the needs of First Nations Children to access “products, services, and supports” (Indigenous Services Canada, 2024) requires the collaboration of both the federal and provincial governments in a timely manner. Mamakwa further indicates his disappointment as the products were a private donation and did not require the spending of provincial funding.

Moon Time Connections, a national organization dedicated to providing menstrual products to Indigenous peoples throughout Turtle Island, shares Mamakwa’s concern. Working with the Ontario chapter of Moon Time Connections, Veronica Brown recognizes the government’s actions as a “colonial barrier” (McGillivray 2021) to equitable access to period products.

Nichole White created Moon Time Connections because she discovered Indigenous students learning in remote and rural areas were missing school due to a lack of access to menstrual products. The first chapter was created in Saskatchewan, previously known as Moon Sisters, and the organization expanded to Ontario, Manitoba, and British Columbia. They actively work toward period equity in collaboration with 120 northern Indigenous Communities from coast to coast.

References

Lane, Heather. 2024. “An Assessment of Menstrual-Related Needs in Northern Communities.” Moon Time Connections. True North Aid. https://truenorthaid.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/An-Assessment-of-Menstrual-Related-Needs-in-Northern-Communities-FINAL.pdf.

McGillivray, Kate. 2021. “MPP Calls out Province’s Free Menstrual Products Plan for Not Including First Nations Schools.” CBC News, October 23, 2021. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/mpp-calls-out-province-s-free-menstrual-products-plan-for-not-including-first-nations-schools-1.6219813.

Plan International Canada. 2022. “Menstruation in Canada – Views and Realities.” Plan International. https://www.multivu.com/players/English/9052951-menstrual-health-day-2022/docs/ViewsandRealities_1653434611799-556425632.pdf.

Toory, Leisha. 2022. “Menstrual Health Is a Public Health Crisis for Indigenous Youth.” Toronto Star, October 13, 2022. https://www.thestar.com/opinion/contributors/menstrual-health-is-a-public-health-crisis-for-indigenous-youth/article_d8f3098b-1a61-52b7-a9c1-a8bdb9dc926d.html.

May 28th is menstrual hygiene day, and this year, the theme is “Together for a #PeriodFriendlyWorld.” While this observance was originally framed as menstrual hygiene – we follow the lead of the World Health Organization, who calls for menstrual health to be recognized, framed, and addressed as a human rights issue, not a hygiene issue. Framing menstruation as such is a reflection of the taboo and stigma around periods. The labelling of period supplies as “feminine hygiene products” is incorrect since as Dr. Jen Gunther explains “needing them is not a sign of being feminine – it’s a sign that you need something to catch blood – and they’re not hygiene products because menstruating is not unhygienic.”

In 2023-2024, the Centre for Human Rights Research at the University of Manitoba has worked on the “Period Poverty & Equity, On Campus and Beyond” project to assess access to period supplies for the University of Manitoba community and to work towards menstrual equity, on campus and in the community. This series of essays is part of the Period Poverty & Equity, On Campus and Beyond project and aims to explore issues of menstrual justice that are often overlooked.

Access to Menstrual Products in Federally Regulated Prisons in Canada

Access to Menstrual Products in Federally Regulated Prisons in Canada

May 30, 2024

Hannah Belec (she/her)

Image: iStock Photo

In December 2023, Employment and Social Development Canada announced that federally regulated employers must now provide pads and tampons to all employees in an accessible location at no cost. The press release from December 15th states that “menstruation is a fact of life” and pads and tampons are “basic necessities.”[1] Yet, current access to menstrual hygiene products in other federally regulated institutions, specifically prisons, certainly does not reflect the Canadian government’s apparent acceptance that “menstruation is a fact of life” and that both pads and tampons are “basic necessities.”[2]

In 2018, Public Safety Canada stated that there were approximately 676 federally incarcerated women.[3] These women make up between 7% and 8% of the total federal offender population and are the fastest-growing federal offender population.[4] For example, despite the total number of federally incarcerated offenders minimally increasing by 0.3% in the past ten years, the number of federally incarcerated women has increased by 20%.[5] Moreover, according to a 2022 study by Corrections Services Canada, there are approximately 21 openly trans-men and 17 individuals who openly identify as gender fluid, gender non-conforming/non-binary, intersex, two-spirited, or unspecified.[6] So, these statistics suggest that there are currently between 700 to 800 federally incarcerated offenders, residing in prisons designated for women and prisons designated for men, who may require menstrual hygiene products at some point during their incarceration, if not regularly – and this number will only continue to increase if the upward trend of federally incarcerated women continues.

In compliance with the United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-Custodial Measures for Women Offenders, or the Bangkok Rules, Canadian federal prisons provide “facilities and materials required to meet women’s specific hygiene needs, including sanitary towels provided free of charge.”[7] However, some prisons designated for women do not provide tampons free of charge, only pads. For example, in a 2017 report conducted by the Senate on womens’ experience in Canadian prisons, incarcerated women at Joliette Prison in Quebec stated that they had to purchase tampons from the canteen if they wanted them, as they were only provided one kind of sanitary pad.[8] The need to buy tampons is a barrier to menstrual equity in Canadian prisons despite the Canadian government stating that pads and tampons are a basic necessity.

Even if a Canadian prison provides both tampons and pads free of charge, many inmates complain that they are not provided enough. On average, menstruators use about 3-6 pads or tampons daily, so three tampons may not be enough for one day, depending on an individual’s flow.[9] Yet, one inmate participant in Dr. Martha Paynter’s reproductive justice workshop exclaimed, “Bring a box! Why don’t they bring a box? You ask for tampons, and they bring you three. We don’t want to ask the male staff for tampons.”[10] Another inmate participant stated that it was “degrading” to ask for more menstrual hygiene products.[11] For incarcerated trans-men and non-binary, two-spirit, or intersex offenders who menstruate, their reluctance to ask male or female staff for menstrual hygiene products is likely exacerbated by feelings of fear, shame, and gender dysphoria. So, all federally incarcerated offenders need free and easily accessible pads and tampons, just like federal employees, to ensure their menstrual hygiene needs are addressed, and their dignity or safety is not compromised.

These economic and gender-specific barriers to menstrual equity in Canadian prisons contradict the government’s assertion that “menstruation is a fact of life” and that both pads and tampons are “basic necessities.”[2] Just like employees of the federal government, all federally incarcerated offenders, in both prisons designated for men and prisons designated for women, need free and easily accessible pads and tampons. This International Women’s Day (March 8th) and Menstrual Hygiene Day (May 28th), let’s advocate for free and accessible menstrual hygiene products in federally regulated prisons alongside federally regulated workplaces – because offenders are humans with rights that must be protected.

References

[3] https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/ccrso-2018/ccrso-2018-en.pdf

[4] https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/cj-jp/state-etat/2021rpt-rap2021/pdf/SOCJS_2020_en.pdf

[5] https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/cj-jp/state-etat/2021rpt-rap2021/pdf/SOCJS_2020_en.pdf

[6] https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2022/scc-csc/PS83-3-442-eng.pdf

[8] https://sencanada.ca/en/sencaplus/news/life-on-the-inside-human-rights-in-canadas-prisons/

May 28th is menstrual hygiene day, and this year, the theme is “Together for a #PeriodFriendlyWorld.” While this observance was originally framed as menstrual hygiene – we follow the lead of the World Health Organization, who calls for menstrual health to be recognized, framed, and addressed as a human rights issue, not a hygiene issue. Framing menstruation as such is a reflection of the taboo and stigma around periods. The labelling of period supplies as “feminine hygiene products” is incorrect since as Dr. Jen Gunther explains “needing them is not a sign of being feminine – it’s a sign that you need something to catch blood – and they’re not hygiene products because menstruating is not unhygienic.”

In 2023-2024, the Centre for Human Rights Research at the University of Manitoba has worked on the “Period Poverty & Equity, On Campus and Beyond” project to assess access to period supplies for the University of Manitoba community and to work towards menstrual equity, on campus and in the community. This series of essays is part of the Period Poverty & Equity, On Campus and Beyond project and aims to explore issues of menstrual justice that are often overlooked.

Abortion is Healthcare Colouring Page

Abortion is Healthcare Colouring Page

June 13, 2025

Aubrey Yuol

Centring the phrase “Abortion is Healthcare”, this colouring page reflects the importance of abortion access and gender equity in the CHRR’s work towards reproductive justice. This printable page is free to use for communities and in classrooms. This artwork was created by Aubrey Yuol.

Contact Us

We’d love to hear from you.

442 Robson Hall

University of Manitoba

Winnipeg, Manitoba

R3T 2N2 Canada

204-474-6453

Quick Links

Subscribe to our mailing list for periodic updates from the Centre for Human Rights Research, including human rights events listings and employment opportunities (Manitoba based and virtual).

Traditional Territories Acknowledgement

The University of Manitoba campuses are located on the original lands of the Anishinaabeg, Ininiwak, Anisininewuk, Dakota Oyate, Dene and Inuit, and on the National Homeland of the Red River Métis.

Centre for Human Rights Research 2023© · Privacy Policy