International Women’s Day (IWD) is recognized by the United Nations (UN) and the international community to celebrate the collective efforts of women – acknowledging the work, the sacrifices, and the social, economic, cultural, linguistic, and political contributions of women to society. Celebrated annually, IWD has its roots in the labour movement when in 1908, 15,000 women marched through New York City to demand better pay, shorter working hours, and the right to vote.[1] The following year, in 1909, the Socialist Party of America declared the first National Women’s Day in the United States. At the 1910 International Conference of Working Women in Copenhagen, 100 women agreed to communist activist Clara Zetkin’s (1857-1933) suggestion of making the day an international observance, and in 1911, International Working Women’s Day was marked for the first time by over a million people in Europe.[2]

After decades of organizing and activism by women, the UN hosted the 1975 World Conference on Women in Mexico, the outcome of which was a ten-year World Plan of Action for the Advancement of Women. This report recognized the significant differences in the experiences of women around the world. It identified the role of women in the “elimination of imperialism, colonialism, neo-colonialism”[3] and outlined recommendations for governments, institutions, organizations, employers and unions, media, non-governmental organizations, and political parties with specific attention to the needs of different groups of women in the fight for equality. As part of this Plan of Action, the UN officially declared March 8 as an international observance. IWD is now celebrated in countries throughout the world, contributing to a growing international women’s movement.

Yet, this time for celebration is tempered by the continued need for organizing, for resistance, and for protest to achieve even the most basic of human rights for women, girls, and gender-diverse people.

In countries around the world, we see the ongoing and alarming assaults against women. Gender-based violence is embedded in heteropatriarchal societies and stands as one of the most widespread human rights violations in the world. Globally, an estimated 736 million women, or one in three women, have been subjected to intimate partner violence at least once in their life,[4] with initial evidence showing that this intensified for women across the globe during the COVID-19 pandemic.[5] It is estimated that in the Canada, as many as 85% of women in prison have experienced childhood abuse[6] and intimate partner violence[7] at some point during their life.

That violence also extends to non-partner violence, and in the Canadian settler colonial context, murdered and missing Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Questioning, Intersex, and Asexual Plus people (MMIWG2S+) is disastrous human rights crisis.

Also owing to ongoing processes of colonialism, and a function of a racist criminal justice system and socioeconomic marginalization, we are witnessing the overrepresentation of Indigenous women in Canadian prisons, with Indigenous women now accounting for almost half of the female inmate population in federally run prisons,[8] despite accounting for less than 5% of the population. For youth, Indigenous girls accounted for 60 percent of all female youth admitted to provincial and territorial corrections systems.[9] This overrepresentation occurs within broader patters of systemic discrimination and incarceration also of Black women,[10] women who are street-involved, and sex workers.

We have witnessed the deliberate targeting of, and violence against, trans women in countries around the world including the transphobic murder of 16 year old Brianna Ghey in broad daylight in February 2023 in the United Kingdom. This transphobic violence exists alongside and perhaps as a result of the rise of anti-transgender rhetoric, laws, and legislation.

We are also witnessing the deliberating targeting of women human rights defenders. In Iran, the death of Mahsa (Jina) Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish woman in September 2022, in the custody of the morality police after being arrested for an “improper” hijab, sparked demonstrations across the country, including in schools and universities. Iranian authorities have used excessive and lethal force in their response to the protests.

The harassment and deliberate targeting of women in politics threatens civil and political rights and is a barrier for their participation, thus threatening democratic process. This harassment, worsened in part by the anonymity afforded by online platforms, is accentuated towards Indigenous and racialized women, both within the political domain but also in the broader society. When Black artist Jully Black performed the Canadian national anthem and showed support to Indigenous peoples by changing one word of the anthem, she was subjected to a barrage of online vitriol. Harassment and discrimination against Muslim woman also demands our attention – a Manitoba-based report on Islamophobia found that 73% of those reporting experiences of Islamophobia were women.[11]

In countries affected by war, such as Ukraine, recent policy papers show the devastating impacts of conflict on women and girls, including as it relates to food insecurity, malnutrition, increased gender-based violence, and refugee flows. Since Afghanistan’s fall to the Taliban in August 2021, there has been systematic violation of the human rights of women and girls, with women’s rights defenders have been deliberately targeted with unlawful detention, and women and girls have been forbidden from attending schools and universities, accessing work, sport and recreation, and public spaces. and women’s rights have been. This is by no means a new or unique phenomenon – the impact of war and conflict on women has been long documented,[12] yet women are also typically excluded from peace negotiations.

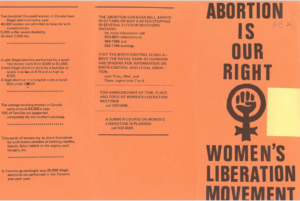

We also see the reversal and dismantling of the legal rights that have been afforded to women in countries around the world. In the United States, the overturning of Roe vs Wade by the Supreme Court in 2022 gives individual states the power to implement laws that can restrict and/or ban access to abortion, with bodily control falling under the purview of the state. This overturning will not stop abortions, but it will undoubtedly stop safe abortions, and the impacts of which will be detrimental to groups of people already systemically marginalized and historically excluded in society, including Black, Indigenous, people of colour, people with disabilities, and LGBTQ+ people.

Women are also experiencing widening economic inequalities, inequalities that have been accentuated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Women are more likely to be in low-wage and precarious employment positions, in undervalued positions and sectors, all while carrying the load of the social reproduction of labour. As an example, care workers in Canada, many of whom were immigrants working in a low-wage sector have faced high rates of COVID infections, widespread job losses, and ongoing and debilitating financial challenges.

The Centre for Human Rights Research (CHRR) at the University of Manitoba was established in 2012 with the goal of supporting and fostering research around human rights, broadly defined. Researchers associated with the CHRR work to address the myriad of ways through which heteropatriarchy, colonialism, and white supremacy have impacted different groups of women. Researchers working with the CHRR have also highlighted those voices that have been deliberately silenced and ignored.

Dr. Jane Ursel is undertaking a longitudinal study to understand why attrition rates in sexual assault cases have been impervious to change. Professor of Law Brenda Gunn has argued for the importance of using a human-rights based approach to understand and address violence against Indigenous women. Dr. Kiera Ladner and Dr. Shawna Ferris are leading the effort to create a digital archive of the Walking With Our Sisters project initiated by Métis artist and activist Christi Belcourt. Dr. Karine Duhamel, Dr. Adele Perry, and Dr. Jocelyn Thorpe have created a podcast (produced by Olivia Macdonald Mager) on some of the links between MMIWG2S+ and dwindling public transit options. Dr. Lindsay Larios works on research exploring issues of reproductive justice in the Canadian context. Dr. Nancy Hansen is a disability rights scholar and activist who explores the employment experiences of women with physical disabilities and disabled women’s access to primary health care. Dr. Julia Smith focuses on the history and politics of women’s labour activism. Dr. Lorna Turnbull leads research projects looking at the leading court decisions regarding motherwork and equality, the overlap between children in the child welfare system and youth in the criminal justice system, and economic supports for caregivers.

Alongside the widespread challenges faced by women and girls in countries around the world, we continue to see, as we always have – women’s resistance. Women are at the forefront in calls to action for gender-based violence, and here in Canada, Indigenous advocate and activists have been relentless in their demands for action. While the US overturned Roe vs. Wade, advances in access to abortion have been made in countries such as Ireland, and with movements such as the ‘Green Wave’ movement in Argentina, Mexico, and Colombia. Women lead the way in climate justice movements, as well as movements for food sovereignty.

IWD’s origins lay in socialist-feminist struggles. Feminist movements that have focused on equal rights have often failed to make substantive change for all women, or account for the ongoing impacts of colonialism on Indigenous women, the experiences of racialized women and girls living at the intersection of racism and misogyny, the impacts of disability, or the particular experiences of trans and non-binary people.

International Women’s Day must go beyond the symbolic. It must work to challenge white supremacy, heteropatriarchy, and settler colonialism and build networks and communities of solidarity and allyship if we are to work towards enacting social and political change for all women. So we can pause to celebrate, and then we, collectively, must continue to do the (primarily unpaid) work.

[1] For an overview of some of the key moments in the history of IWD, and in the labour movements that were crucial in its development, including prior to 1908, see: www.un.org/en/observances/womens-day/background

[2] Bianca Walther. “Once Upon a Time In Copenhagen.” aiic.org. March 08, 2021. Accessed March 07, 2023. https://aiic.org/site/blog/once-upon-a-time-in-copenhagen.

[3] United Nations. Report of the World Conference of the International Women’s Year. Mexico City, 19 June-2 July 1975. Available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N76/353/95/PDF/N7635395.pdf?OpenElement. Accessed March 07 2023.

[4] World Health Organization, on behalf of the United Nations Inter-Agency Working Group on Violence Against Women Estimation and Data (2021). https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/02/background-paper-synthesis-of-evidence-on-collection-and-use-of-administrative-data-on-vaw

[5] UN Women. (2020). Intensification of efforts to eliminate all forms of violence against women: Report of the Secretary-General (2020), p. 4.

[6] Bodkin, C., Pivnick, L., Bondy, S.J., Ziegler, C., Martin, R.E., Jernigan, C. and Kouyoumdjian, F. (2019). History of Childhood Abuse in Populations Incarcerated in Canada: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Public Health 109, e1_e11, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304855

[7] Prison Facts in Canada. (2017/2018). Available at: www.womensprisonnetwork.org/Facts.htm. Accessed March 7, 2023.

[8] McGuire, M. M., & Murdoch, D. J. (2022). (In)-justice: An exploration of the dehumanization, victimization, criminalization, and over-incarceration of Indigenous women in Canada. Punishment & society, 24(4), 529-550.

[9] Statistics Canada. 2018. “Adult and youth correctional statistics in Canada, 2016/2017”.

[10] Owusu-Bempah, A., Jung, M., Sbaï, F., Wilton, A. S., & Kouyoumdjian, F. (2021). Race and Incarceration: The Representation and Characteristics of Black People in Provincial Correctional Facilities in Ontario, Canada. Race and Justice, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/21533687211006461

[11] Sotiriadou, E., and I. Elbakri. (2022). Friendly Manitoba: Community Experiences With Islamophobia. Manitoba Islamic Association. Available at: www.miaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/report-4-6.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2023.

[12] For more information, see: UN Women. (2002). Women, War, Peace: The Independent Experts’ Assessment on the Impact of Armed Conflict on Women and Women’s Role in Peace-Building. Vol 1: www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2002/1/women-war-peace-the-independent-experts-assessment-on-the-impact-of-armed-conflict-on-women-and-women-s-role-in-peace-building-progress-of-the-world-s-women-2002-vol-1; Radio show “Women in Wartime with Cynthia Enloe”: https://safespaceradio.com/the-experiences-of-women-in-war/