(from left): Albert McLeod/Two-Spirited People of Manitoba Inc; The REDress Project (University of Toronto, 2017),

artist Jaime Black/photographer Sam Javanrouh; Canadian Union of Postal Workers; Charles Edward Miller/cemillerphotography.com

Reproductive and Bodily Justice: The Foundations of Gender Equity

By Felicia Sinclair

With contributions from Angela Ciceron, Emma Cowman, Adele Perry, Kelly Pugh, and Pauline Tennent.

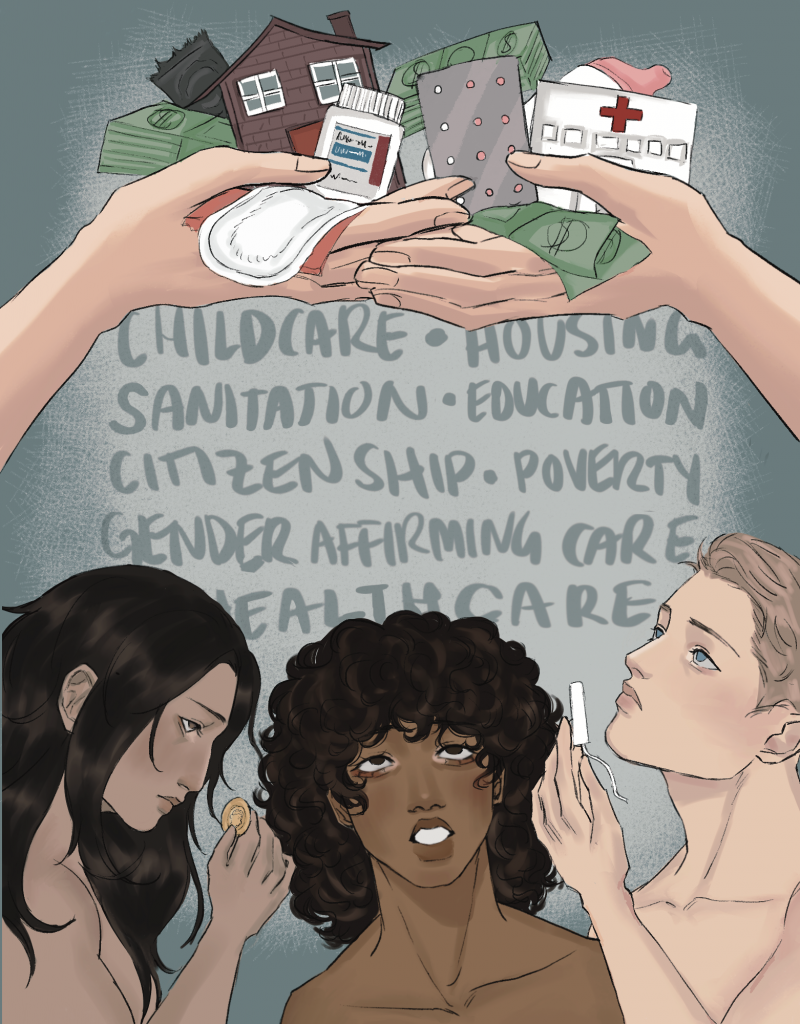

Reproductive and bodily justice encompasses a broad vision of autonomy, care, dignity, health, and justice. Expanding beyond the narrow focus of sexual and reproductive rights, reproductive and bodily justice is rooted in the activism of Black feminists, particularly the work of SisterSong and activists like Loretta J. Ross and Rickie Solinger in the United States, as well as scholars and activists such as Jessica Danforth, Ellen Kruger, Erica Violet Lee, Sarah Nickel, Linda Taylor, and Tasha Spillett here in Canada. It integrates a social justice and human rights lens to examine how social, economic, and political structures shape individuals’ ability to make informed choices about their bodies, families, and futures, including key concepts of autonomy and consent.1 Unlike traditional reproductive rights frameworks, which often focus on legal protections, reproductive justice emphasizes the need for systemic change to create the material conditions necessary for true reproductive freedom. This includes access to safe housing, living wages, education, and culturally competent care, and recognizing that reproductive decisions do not exist in isolation from broader social realities including the intersecting nature of capitalism, white supremacy, and colonialism.2

The Centre for Human Rights Research (CHRR) at the University of Manitoba has a longstanding history of contributing to the research landscape in the area of reproductive and bodily justice, including on topics such as assisted human reproduction, sexual violence at post-secondary institutions, sex work laws, queer and trans health, and menstrual justice. Influenced by scholars and activists working towards reproductive justice, this work at the CHRR is deeply intersectional – systems of oppression intersect to determine who has access to reproductive healthcare, who faces barriers, and who is denied autonomy over their own body. Factors such as race, class, gender identity, geography and spatial aspects, disability, migration status, and colonial histories intersect to restrict access, choice, and autonomy.

“These problems of exclusion cannot be solved simply by including Black women within an already established analytical structure. Because the intersectional experience is greater than the sum of racism and sexism, any analysis that does not take intersectionality into account cannot sufficiently address the particular manner in which Black women are subordinated.”

Crenshaw 1989

How to Cite: Sinclair, Felicia. (2025). Reproductive and Bodily Justice: The Foundations of Gender Equity. Centre for Human Rights Research. https://chrr.info/research-themes/research-themes/reproductive-and-bodily-justice/

What is Reproductive Justice?

Reproductive justice has as its foundation the “human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy, have children, not have children, and parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities.”3 The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (1979) defines reproductive rights as the right to choose the number and spacing of your children, as well as having access to the information, education and means to enable these rights.

Reproductive justice is firmly grounded in a human rights framework. International human rights frameworks affirm that reproductive autonomy is essential to human dignity, and restricting it constitutes a violation of fundamental rights. It is deeply interconnected with the broader struggles for racial, economic, and environmental rights. Reproductive justice is foundational to gender justice, recognizing that systemic inequalities shape people’s ability to exercise autonomy over their bodies and reproductive choices. A reproductive and bodily justice approach demands not only legal protections but also the material conditions that enable people to make real choices about their bodies and futures. Socioeconomic disparities continue to significantly affect access to reproductive healthcare, limiting many individuals’ ability to make empowered choices and shaping a person’s autonomy.4,5 As such, reproductive justice emphasizes not only choice, but access.

In terms of access, marginalized populations often face barriers to reproductive rights because they confront intersecting social, economic, geographic, spatial, and political disparities and structures of oppression.6,7 These barriers manifest in the experiences of marginalized women, such as those who are incarcerated or those who are undocumented, in accessing reproductive care. Colonialism continues to structure Indigenous people’s access to abortion.1

In light of these barriers, community support networks are vital, and often subsidize the role of the state in providing essential resources, emotional support, and safe spaces for individuals navigating reproductive decisions. These processes of care are referred to as ‘care work’, encompassing the paid and unpaid labour of care and reproduction that occurs in the home and the community. Because it occurs in the home, care work is often invisible, undervalued, and naturalized as “women’s work”. As a gendered and racialized phenomenon, care work is disproportionately undertaken by women of colour. Historically, this was seen in the role of enslaved Black women as domestic labourers in the U.S8, and today, in the migrant women performing care labour in countries such as Canada9.

Areas of Reproductive Justice

Autonomy and Consent

Working towards reproductive and bodily justice requires an understanding of community. It also requires an understanding of autonomy and consent. Autonomy is a central concept in ethical theories and is the principle that individuals should be self-governing.10 Autonomy considers not only freedom of choice, but also access to the information on which to base a decision, as embodied in the principle of informed consent.11 Autonomy and consent are intertwined with power dynamics, and there are numerous examples, historic and contemporary, of individuals who are marginalized by various systems of oppression being coerced in their healthcare decisions. However, human rights frameworks also remind us that we must balance individual autonomy with the collective well-being of the community, striking a delicate balance between societal harmony and individual autonomy.

Bodily justice is crucial for reproductive rights and expands the concept of autonomy and consent to focus on bodily integrity and the moral dimensions of bodily integrity, highlighting the need to respect the rights of people over their bodies. The denial of bodily autonomy can cause significant damage, highlighting the importance of a strong legal and ethical framework for the protection of these rights.12 Court rulings regarding the constitutional rights of individuals – particularly pregnant individuals – to make decisions about their bodies continue to be debated to great degree within today’s political landscape, reinforcing the necessity of safeguarding bodily autonomy.

The overturning of Roe v. Wade by the Supreme Court of the United States on June 24, 2022 in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization was shocking and will undoubtedly have long term consequences. It also seems to indicate a resurgence of attempts to legitimate control – through law – over the lives and bodies of women, girls, and other people who can become pregnant, especially those without the means to travel in order to access abortion services. Of course, this is not a new concept to many people. Forced and coerced sterilization of Indigenous women, lack of access to abortions in rural and northern communities, and ongoing systemic racism in the healthcare system shows that Canada is no utopia, nor a model for reproductive rights or justice.

According to the Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada (ARCC), there are the same amount, if not more, Crisis Pregnancy Centres (CPCs) than abortion providers in Canada. These CPCs are anti-abortion organizations that present themselves as clinics or counselling centres, and they provide misleading information regarding abortions and use unethical tactics to convince pregnant people not to get abortions. The history of colonization in Canada also plays a significant role, specifically in regard to the bodily autonomy and consent of Indigenous, racialized, and marginalized communities, who have been the target for coercive policies, medical violence, and the denial of reproductive self-determination. Trans men and non-binary people are often excluded from government and healthcare institution data sets, which is an ongoing issue that is compounded by the fact that the rights of the 2SLGBTQ+ community are increasingly coming into the crosshairs.

Struggles for Reproductive Justice

Struggles for reproductive justice do not only drive social movements but occur within them. From its inception, mainstream discourses on reproductive rights often overlooked the needs and experiences of racialized communities and gender diverse folks, and as such, marginalized groups encountered significant challenges in asserting their reproductive rights. Black, Indigenous, and racialized scholars and activists have worked to disrupt pre-existing narratives around reproductive rights, centering the experiences of those who have been, and continued to be, marginalized. These struggles cannot be separated from broader systems of colonialism and state control, particularly evident in the intersections of reproductive justice with child welfare systems that have historically and disproportionately targeted Indigenous and racialized families.

Today, the struggle for reproductive justice continues as reproductive and bodily autonomy remain under constant threat. We are witnessing strong pushbacks, both globally and locally. In Canada, we are witnessing a lack of access to abortion and reproductive healthcare, healthcare shortages, a lack of sexual education, and systemic discrimination that continue to restrict access to all. Globally, the erosion of reproductive rights, such as the reversal of Roe v. Wade in the U.S., and growing anti-gender, anti-LGBT, anti-abortion rhetoric, as well as authoritarianism, shrinking space for civil society, and patriarchal and misogynistic gender norms and power structures are all factors that demand our attention.

1Monchalin R, Pérez Piñán AV, Wells M, Paul W, Jubinville D, Law K, et al. A qualitative study exploring access barriers to abortion services among Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Contraception. 2023 Aug;124:110056.

2Yee J. Reproductive Justice [Internet]. 2010. Available from: https://jolocas.blogspot.com/2011/11/reproductive-justice.html

3SisterSong. Reproductive Justice [Internet]. n.d. Available from: https://www.sistersong.net/reproductive-justice

4Loder CM, Minadeo L, Jimenez L, Luna Z, Ross L, Rosenbloom N, et al. Bridging the Expertise of Advocates and Academics to Identify Reproductive Justice Learning Outcomes. Teach Learn Med. 2020 Jan 1;32(1):11–22.

5Ross LJ. Reproductive Justice as Intersectional Feminist Activism. Souls. 2017 July 3;19(3):286–314.

6Ross LJ, Solinger R. Reproductive justice: an introduction. Oakland, Calif: University of California press; 2017. (Reproductive justice).

7Larios L, Ahonon MP, Elias H, Halldorson E. Migrant Reproductive Justice: Experiences of Uninsured Pregnant People in Manitoba, Canada. Winnipeg: Manitoba Association of Newcomer Serving Organizations; 2025 Mar.

8Davis AY. Women, Race, and Class. New York: Vintage Books; 1983.

9Tungohan E. Contextualizing Care Activism. In: Care Activism: Migrant Domestic Workers, Movement-Building, and Communities of Care. Chicago: University of Illinois Press; 2023. p. 19–62.

10Beauchamp T, Childress J. “Principles of Biomedical Ethics”: Marking Its Fortieth Anniversary. Am J Bioeth. 2019 Nov 2;19(11):9–12.

11Faden RR, Beauchamp TL, King NMP, editors. A history and theory of informed consent. New York: Oxford University Press; 1986. 392 p.

12Mackenzie C, Stoljar N, editors. Relational Autonomy: Feminist Perspectives on Autonomy, Agency, and the Social Self [Internet]. Oxford University PressNew York, NY; 2000 [cited 2025 June 9]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/book/49675

13Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Univ Chic Leg Forum. 1989;141:139–67.

14Mohammed Tohit NF, Haque M. Empowering Futures: Intersecting Comprehensive Sexual Education for Children and Adolescents With Sustainable Development Goals. Cureus [Internet]. 2024 July 22 [cited 2025 June 9]; Available from: https://www.cureus.com/articles/274971-empowering-futures-intersecting-comprehensive-sexual-education-for-children-and-adolescents-with-sustainable-development-goals

15Gonzales G, Henning‐Smith C. Barriers to Care Among Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Adults. Milbank Q. 2017 Dec;95(4):726–48.

16Coen-Sanchez K, Idriss-Wheeler D, Bancroft X, El-Mowafi IM, Yalahow A, Etowa J, et al. Reproductive justice in patient care: tackling systemic racism and health inequities in sexual and reproductive health and rights in Canada. Reprod Health. 2022 Dec;19(1):44, s12978-022-01328–7.

17Henderson S, Horne M, Hills R, Kendall E. Cultural competence in healthcare in the community: A concept analysis. Health Soc Care Community. 2018 July;26(4):590–603.

18Stone R. Pregnant women and substance use: fear, stigma, and barriers to care. Health Justice. 2015 Dec;3(1):2.

19Sasser JS. At the intersection of climate justice and reproductive justice. WIREs Clim Change. 2024 Jan;15(1):e860.

20Willow A. Indigenous ExtrACTIVISM in Boreal Canada: Colonial Legacies, Contemporary Struggles and Sovereign Futures. Humanities. 2016 July 15;5(3):55.

21Bernauer W. The Duty to Consult and Colonial Capitalism: Indigenous Rights and Extractive Industries in the Inuit Homeland in Canada. North Rev [Internet]. 2023 Mar 6 [cited 2025 Aug 21];54. Available from: https://thenorthernreview.ca/index.php/nr/article/view/997

22Basu N, Lanphear BP. The challenge of pollution and health in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2019 Apr;110(2):159–64.

23Deaton BJ, Lipka B. The provision of drinking water in First Nations communities and Ontario municipalities: Insight into the emergence of water sharing arrangements. Ecol Econ. 2021 Nov;189:107147.

Affiliate Researchers

Related Resources

Explore More Research Themes

-

Borders & Human Rights Theme

FIND OUT MORE -

Water Rights & Justice Theme

FIND OUT MORE -

Indigenous Peoples & Human Rights Theme

FIND OUT MORE -

History & Commemoration Theme

FIND OUT MORE

Support Us

Whether you are passionate about interdisciplinary human rights research, social justice programming, or student training and mentorship, the University of Manitoba offers opportunities to support the opportunities most important to you.